Cantwell's Concept Art

Colin Cantwell opens up about his work on Star Wars, and shares never before seen concept art.

It's the ship that made the Kessel Run in less than twelve parsecs.

The Millennium Falcon is the most famous starship of all time, and a bonafide cultural icon in its own right.

But it underwent a long and arduous conceptual phase before that final iconic shape emerged; the one now blasting its way across the big screen once again. In fact it wasn't even known by its famous name until well into production, having up until then gone under the much more mundane moniker: Pirate Ship.

The conceptualization mythology as it has been related down through the decades since the film first blared across cineplexes goes that the final design, perhaps best described as a ‘mandible’d saucer’, was one Lucas had found in a burger with a bite taken out of it, and an olive pinned to its side.

Voila; Falcon.

There are variations of that story. In some versions he was eating a burger at the time, in others he saw someone eating a burger. The gist remains the same and much like the dog-as-copilot origin story of Chewbacca it's compelling enough that it will likely stay around as part of Star Wars lore forever.

However, I don't buy it.

The Falcon's conceptual development has always intrigued me because exactly how it came to be has never been clearly laid out. I've researched this subject extensively over years and it's only recently I've been able to make out some sort of sensible process.

So this then is The Complete Conceptual History of The Millennium Falcon or How I Started Worrying and Lost My Mind Completely Over a Fictional Spaceship Someone Please Do Something Send Help Why Are You Still Reading Someone Do Something.

From the Adventures of Luke Starkiller, Third Draft:

52. INT. MOS EISLEY SPACEPORT – DOCKING AREA 23

Chewbacca leads the group along a tall gantry overlooking a long Rube Goldburg[sic]-pieced together contraption, which can only be loosely called a spaceship. Luke gives Old Ben a skeptical look. Old Ben just smiles. As they approach the ship, it looks even more homemade and shabby than it did at a distance. The Wookiee calls out to someone inside the ship, but there is no reply.

LUKE

What a piece of junk. This ship isn’t going to get us anywhere!

A tall figure steps out of the shadows of the imposing spacecraft.

This is HAN SOLO, a tough James Dean style starpilot about twenty-five years old. A cowboy in a starship — simple, sentimental and cocksure of himself.

HAN

This ship has been to Terminus and back. There isn’t anyplace she can’t go. She may not look like much, but she’s special. I built her myself, and there is nothing faster… What can I do for you?

In short order, you'll get to know the work of artist and model maker Colin Cantwell who worked on Star Wars. In 2014 he put up for auction a swath of material which hadn't been seen, and as far as I know even heard of, for nearly forty years, including a heap of concept art which either preceded or was at least concurrent with the work of artist Ralph McQuarrie.

We'll touch on some of Cantwell's artwork later on, but first we have to turn our attention to a very special piece of yellow legal pad paper which was part of that auction but which — it turned out afterwards that contrary to what the auction listing said — was not from Cantwell's hand.

Lucas sketching concepts at Ralph McQuarrie’s house (photo by Ed Summer).

Cantwell’s Dart, or X-Wing as he dubbed it.

This is in fact from the hand of George Lucas on his characteristic yellow legal pad. It's a list of ships for Cantwell to begin work on, which given that Cantwell was the first creative hire, makes this the earliest conceptual artwork for Star Wars, and therefore the holy grail for nerdy space fantasy historians.

Cantwell had been hired to work on the ships and vehicles while Lucas was busy finding other early hires like Ralph McQuarrie who would start soon after, and the spaces necessary to get the films made.

It’s too much to unpack everything in this Falcon-centric piece without going off the rails, but since this is the first time I get to address it, here are a few notes

Cantwell’s landspeeder, possibly RF-2?

RF-1 (Dart) – Per Sierra Dall via email, Cantwell’s partner of many years, Cantwell was inspired by the game of dart, which he used to play in a pub in England, possibly when he worked on 2001: A Space Odyssey. now you know what inspired the X-Wing (a name Colin Cantwell came up with)

RF-2 (Stingray) never made it, but it is circular, so maybe it shows the saucer shape already on Lucas's mind? It’s possible this turned into the circular landspeeder design, which eventually was replaced by a Flash Gordon inspired design instead.

RF-3 (WWII Torpedo Fighter) Colin design. The drawing seems to depict (abstractly) the cockpit of a ‘TBF Avenger’ torpedo bomber, indicating the positions of the people, with the circle on the right being the rear-facing gun turret. The ‘colin design’ (or colon, but that doesn’t seem to make sense) in the text seems to indicate that Cantwell already had the Y-Wing design ready at this point, positioned as a bomber of sorts.

I-111 (Finned Sausage). Yes, that’s what it says! Moreover, it lists “Stainless Steel Rat”, which is now our verified inspiration for the TIE Fighter, probably by way of Cantwell.

Published by Four Square Books in 1966, 1973, 1974, 1976 & 1978, cover by Eddie Jones — Source.

A history of the TIE Fighter is out of scope, so I'll come back to it at some later date. But I think it's safe to say that 'Finned Sausage' will sit with us all for years to come. Here's Colin Cantwell's subsequence drawing.

Our main focus however are items C and D, Rebel Blockade Runner, the ship that opens the film as we know it today, and Pirate Ship, a moniker it would carry throughout most of development, until it was finally renamed The Millennium Falcon.

The original Star Wars story went through a lot of changes as Lucas worked out its kinks, turning it from a hot mess into the story that became the final film (a process which continued throughout production, and arguably to this day), and those continuing changes makes it hard at times to know when what occurred.

What this piece of yellow paper tells us, is that the Rebel Blockade Runner and the Pirate Ship were concurrent, but that Lucas seemed in two minds regarding which one was supposed to have the "longish" design he had found. First it was the Blockade Runner, but then right after he seems to have changed his mind to the Pirate Ship. An ironic decision as we'll see later, when outside influence forced him to change his mind back.

He also wrote “see book cover”, although we have no idea which book is referring to. He clearly had something very specific in mind since the note is right next to that drawing (and so the sci-fi book cover trawling begins anew). This along with the Stainless Steel Rat reference reaffirms Lucas's approach to developing ideas and visual starting points, by trawling every science fiction book and magazine he could get his hands on.

We'll remember this bit later on, but for now, let's get introduced to our cast.

About a year and a half into his space fantasy screenplay, George Lucas hired one of the first creatives to help flesh out the world of Adventures of the Luke Starkiller. The studios didn't get what Lucas was selling, and his best bid was to jump start their imaginations with some visuals.

Colin Cantwell and George Lucas inspecting an early Y-Wing model

Colin Cantwell, who started “a few days or weeks” before Ralph McQuarrie (according to McQuarrie himself) in November of 1974, had worked with Stanley Kubrick on realizing many of the extremely complicated effects on 2001: A Space Odyssey. He was an avid spaceship nut, a model maker and a painter to boot; a perfect fit for Lucas's space film.

He immediately set to work bringing bringing the screenplay's many vehicles to life, starting with the Y-Wing and working his way through the X-Wing, the landspeeder, the Death Star, the Jawa Sandcrawler and the so-called Pirate Ship and finally the Rebel Blockade Runner.

Cantwell is an intriguing person in his own right, and I highly recommend Jason Debord's video interviews which explore his varied career, including his work for NASA, CBS, Kubrick, Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, War Games and much more.

Says Joe Johnston:

Colin deserves a lot of credit for the initial vision of what A NEW HOPE looked like, at least in the form of its hardware. It's true that all his designs were re-designed to a varying degree but a strong Cantwell influence shows through on most of them.

If the primordial ooze of Star Wars is Lucas's mind, then the following Ralph McQuarrie sketches are what crawled out of it.

Sketched on the day he received the screenplay, they represent some of the earliest visual developments on Star Wars.

The first sketch was the very first drawing McQuarrie made for Star Wars. But it is the following two, also made on that first day, that are of particular interest to us as they bear a resemblance to what we will become key to understanding the evolution of the Pirate Ship and Rebel Blockade Runner.

Note the rearward engine cluster, the elongated shape, the possibly spherical cockpit and just behind that (on the second sketch), two protruding 'pods'.

Ralph McQuarrie was another early hire and perhaps contributed more than anyone else bar Lucas himself to the success of Star Wars. The exact division of labor in the concept art department hard to decipher, but we'll do our best to navigate the design process some forty years hence.

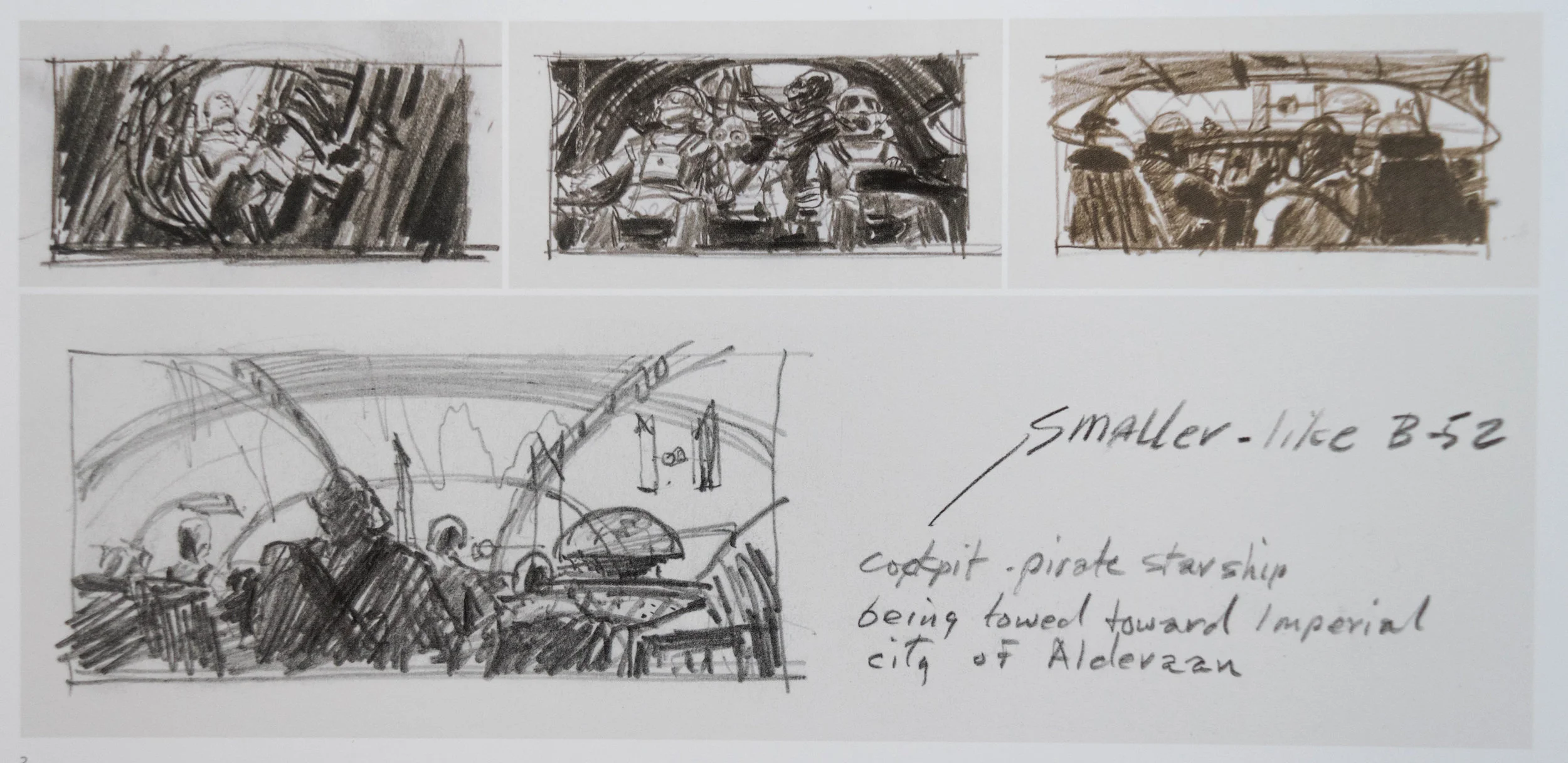

First up is a sheet of paper with a number of doodles on it, about half of which look to be related to explorations around the Pirate Ship cockpit, with the one on the far left having the following note next to it: cockpit pirate starship (smaller like B-52) being towed toward Imperial city of Alderaan. These sketches pretty much nail the general layout of the cockpit that will make its way to the screen (and there's even what looks like a gunport in there).

The sketch in brown pencil seems to line up pretty well with the ship seen in the following series of very early storyboards.

B-52 Cockpit

The following sketches, most of them from The Ralph McQuarrie Archives (2007) — although the second one is from Making of Star Wars (2010) — were described by McQuarrie himself as being specifically of the Millennium Falcon, although for the sake of correct chronology, they are from the period when it was still referred to as the Pirate Ship.

This sequence, which would survive to the final film, albeit changed, shows the Pirate Ship being overtaken by imperial Star Destroyers and escorted by TIE Fighters to the Imperial prison facility. The ordering of these might be slightly off; they have never appeared together before as far as I know. They may also have been conceived at different times, although as far as I can tell they all depict the same proto-Pirate Ship design, which must have been a very early iteration as it appears in no other paintings or models; so I put these sketches close together in conception.

A couple of these shots (#2 and #8) eventually wound up as production paintings (we'll revisit both later in this article).

What's remarkable about these sketches is their depiction of a ball-like cockpit design which only shows up here, and as such are likely to be some of the first rough thoughts around what a design might look like. Although it is rather undefined and rough, it strikes me as almost Flash Gordon-like.

Shown here, the first two stills are from the 1930s production, and the right-most (which looks exactly like McQuarrie's first sketch) is from the 1954 production.

Perhaps this approach was dropped because the spherical cockpit was too similar to The Discovery from 2001: A Space Odyssey (see below)?

Elements from the Discovery crop up in many of the subsequent designs nevertheless. The slit cockpit window and a similar engine cluster appear on the final Blockade Runner design, the mid-ships radar dish appears both there as well as on the Falcon design itself. Storyboard artist Alex Tavoularis also adopted the engines for his storyboards (see later).

Another thing that Star Wars brought over from 2001: A Space Odyssey was the real-world NASA-like look and feel which lent Kubrick's seminal 1968 film its air of authenticity. The panels in varying greys and the kitbashed surfaces of the 2001 vehicles was a template for all many science fiction films to come, even ones with a fantasy bent. And worth remembering, aside from 1972's Silent Running and NASA's actual endeavors, 2001: A Space Odyssey's spaceships were just about the only realistic-looking spaceships around before Star Wars.

Furthermore Star Wars's famous reveal of the Blockade Runner is shot nearly identical to The Discovery's reveal in 2001 (only flipped horizontally and sped up about fifty times). That inverted shot comparison might not be a conscious choice, yet it establishes the relationship between the two films (one going this way, another that, one slow, the other fast), and therefore two very different eras of silver screen science fiction.

When exactly the models and the following drawings were done is hard to ascertain since only Ralph McQuarrie had good discipline around dating his paintings, and so we're left to our own devices to figure out the exact progression. But Cantwell went to work and dreamt up a Pirate Ship model, and this is where it gets complicated.

As stated earlier, a timeline is hard to define for these things, but based on how the rest of the design phase ends up playing out, I feel like the next step might have been this drawing by Joe Johnston, primarily because it carries a number of design elements that are also in the later design, yet lacks a number of elements which once introduced made their way through the rest of the timeline (the cross-sectional cylinder, which you can almost see beginning here, as well as the radar dish), which indicates it might be an inflection point.

It's possible Johnston made this design without even having seen Cantwell's first model; after all it serves almost as a fresh start, rather than a continuation, and could just as well have drawn only from the script's description.

Combine this Johnston's cockpit and broad rectangular rear with Cantwell's hexagonal notions and it begins to look like something we're familiar with.

Colin Cantwell seems to have iterated on the above sketch with a plan drawing of the ship, which would be revised before it was made into a model (although Tavoularis's storyboards further down the page carry over this design).

Cantwell’s drawing, similar to McQuarrie’s plan drawing further down, lays out where the locations required by the screenplay would be. Noteworthy that this version has the same extruded pods as McQuarrie had drawn on his first day. Given that Cantwell had started a “a few days or weeks” before McQuarrie, it's possible that this plan drawing preceded McQuarrie.

It's unclear exactly what the steps were to get from the above to the actual model. If I were to venture a guess, the above plan was done very early on in the process and Tavoularis might have served as an interim concept artist for Cantwell. That's entirely speculative however.

The protruding gun turrets also show up in this drawing for ‘shot 3’ from ILM, which was used to calculate costs for shooting the effects sequences.

We'll revisit this design shortly again in a moment, but now the second Cantwell model is beginning to look like something we might recognize.

Notice in this iteration the detailing around the gun ports just behind the cockpit, which echo the B-17 gun ports Lucas had seen in Howard Hawks' Air Force (1943), as well as the aforementioned escape pods in red (three of which are missing).

Colin Cantwell's Pirate Ship model, sans cockpit, with Joe Johnston lingering on the sidelines.

Cantwell's models were used to sell the befuddling screenplay, but Lucas also started bringing on storyboard artists, the first of which was Alex Tavoularis (hired mid-February 1975).

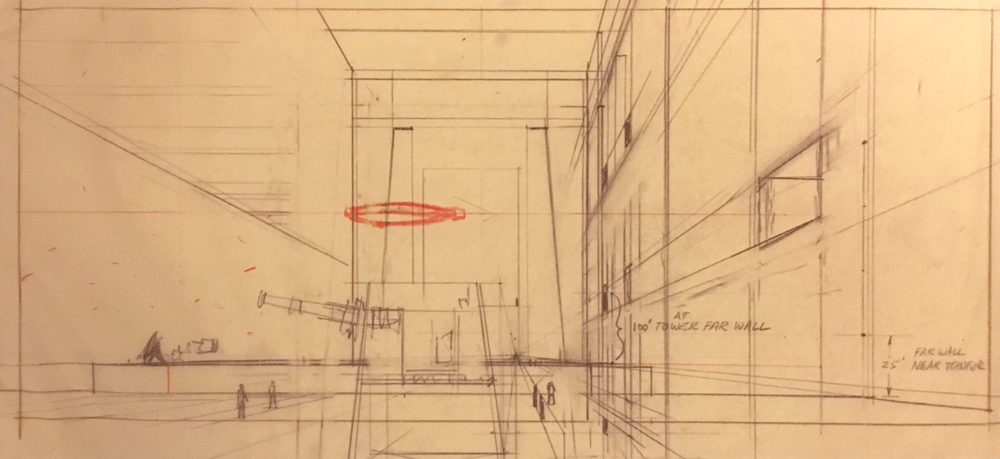

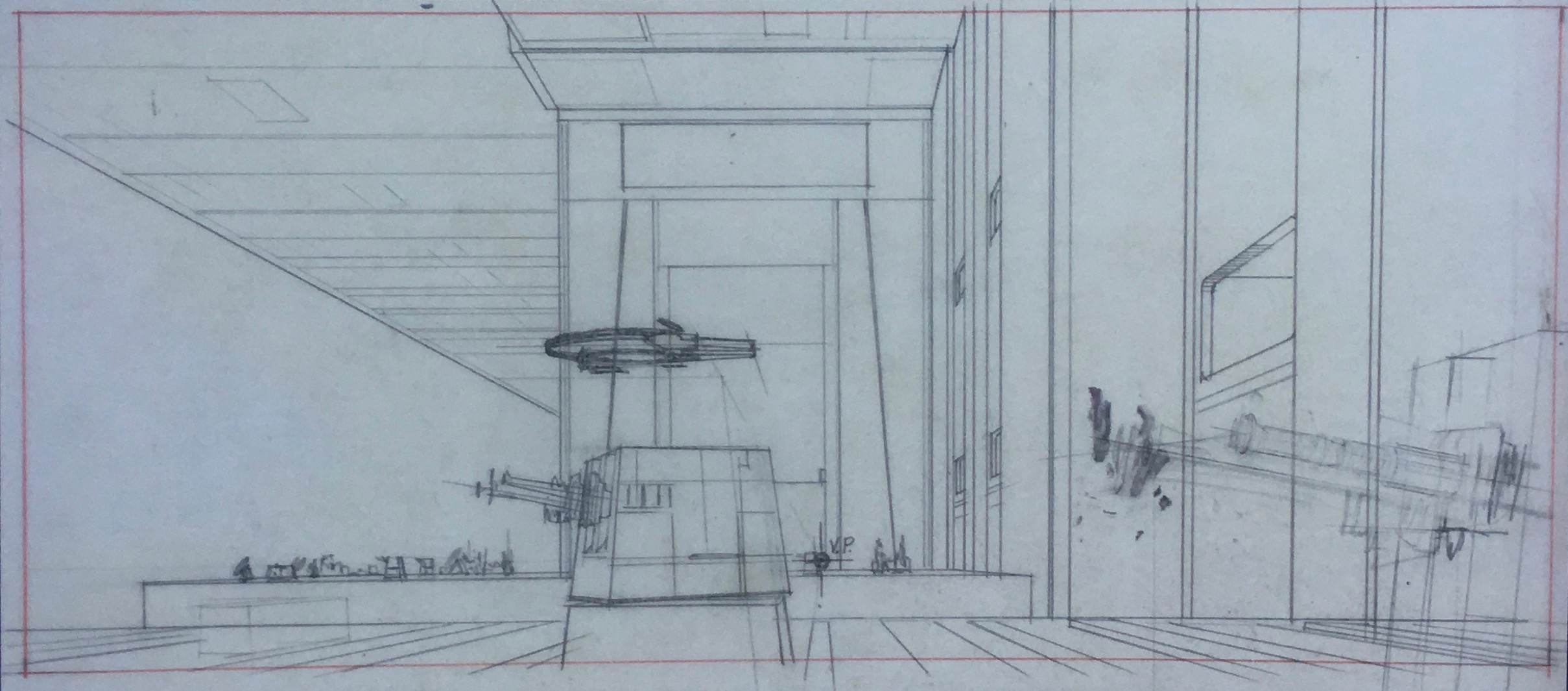

Here follows a mix of storyboards from the opening of the film, showing the ‘Princess Ship’ or Rebel Blockade Runner, as well as a sequence showing the Pirate Ship arriving at the Imperial prison on Alderaan, a location which was later combined with the Death Star (the floating city concept of course ended up as Cloud City in The Empire Strikes Back).

They are presented in the order they appear in Star Wars Storyboards (I've left out non-starship boards) and it soon becomes obvious just how fluid the two designs seemed to be at this stage of production.

Presumably there was a bit of overlap between these projects as the design was getting settled on, and Tavoularis would bring over whichever details he remembered from when he last saw the model, or from on-going conversations between Lucas, McQuarrie, Johnston, Gary Kurtz and anyone else around.

Similarly the cockpit goes from one that is similar only in overall shape to Cantwell's second design, but with different windows (suggesting perhaps that Johnston's drawing came first, since it doesn't show the cockpit from the front), to one that is similar to the second Cantwell model (with slitted windows all the way around the cockpit), to the final one, which is more akin to what we know as the actual Falcon cockpit.

Notice the second-to-last storyboard, with its curved prison facility perimeter and the Chris Foss-like engine scoops.

That design seems to show up in the background of a single Ralph McQuarrie painting which was logged as finished on March 28th, 1975, as well as the last storyboard which looks a lot like a later McQuarrie painting.

Ralph McQuarrie finished this painting on March 28, 1975

McQuarrie's preliminary sketch.

Tavoularis was copying McQuarrie's designs for the storyboards since he isn't listed as a design credit.

This McQuarrie sketch for his first production painting featuring the Pirate Ship in detail seems to share the front half of its design with Cantwell's second model, but also introduces some new touches, such as the cylinder-like swirl mid-ships and what seems to be notion of the rectangular engines that we haven't seen yet.

The difference in profile in particular is a giveaway that something significant happened to the design at this stage.

McQuarrie's sketch has the flat and almost boring profile from Cantwell's design, but the actual painting has a much more bulky profile.

It's a little unclear when the final elements for the next stage fell into place, although McQuarrie did a number of pencil-drawn explorations for this scene (right). For instance, it's around this time the engine configuration changes from the Cantwell model’s grey plates to the rectangular-cylinder-cluster engine, for lack of a better description.

Above is a McQuarrie sketch which fits in here somehow. The turrets are still right behind the cockpit as in earlier versions, but unlike the following painting, yet its profile is different from the earlier versions.

It's also the first time we see the midships cylinder, which wound up making its way through both to the Blockade Runner as well as to the final Millennium Falcon model. And lastly the iconic radar dish is introduced for the first time.

McQuarrie himself noted on the following painting that he “added a lot of surface detail”, which I take to mean that he was the one who took the design from the Cantwell model to this next step.

The gun ports have moved from the ‘neck’ to the cylinder aft of midships and the escape pods have gone from spherical to angular (down to two from three on either side).

Somewhat confusingly, the engine section looks at first glance like the later Blockade Runner configuration, yet upon closer inspection seems to have some sort of tapered cylindrical main engine, elaborated on only in the blueprint, but seemingly nowhere else.

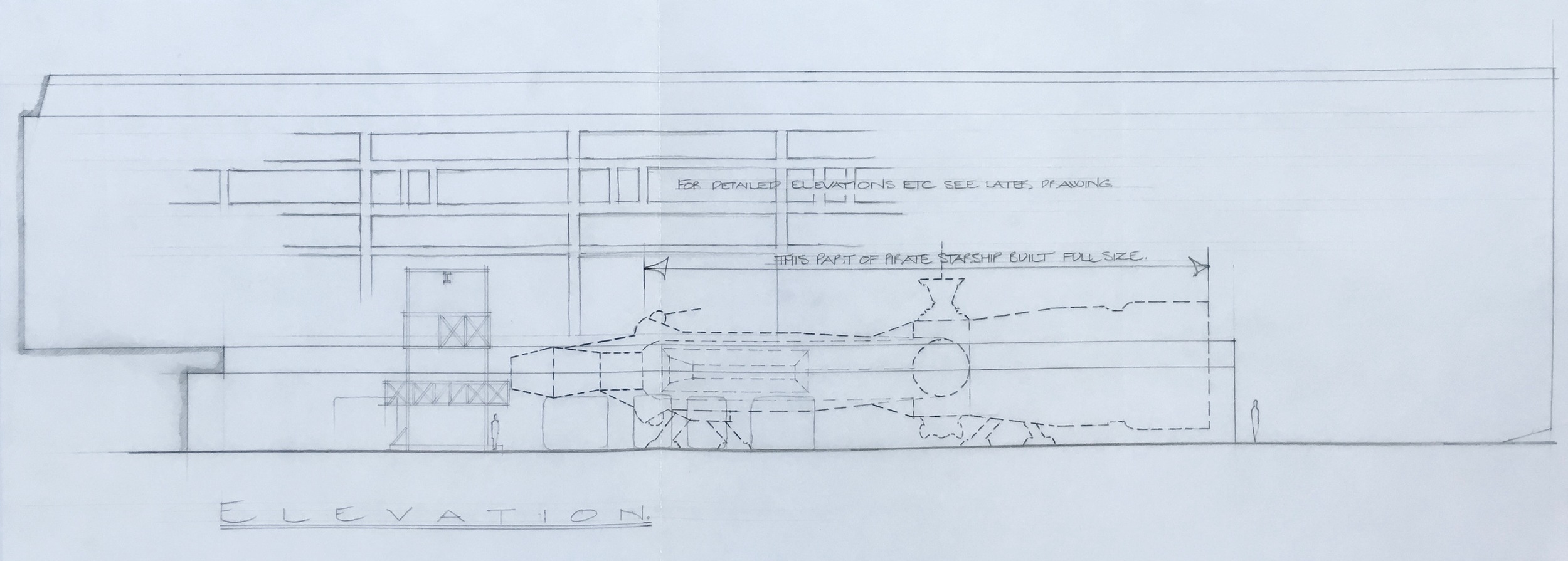

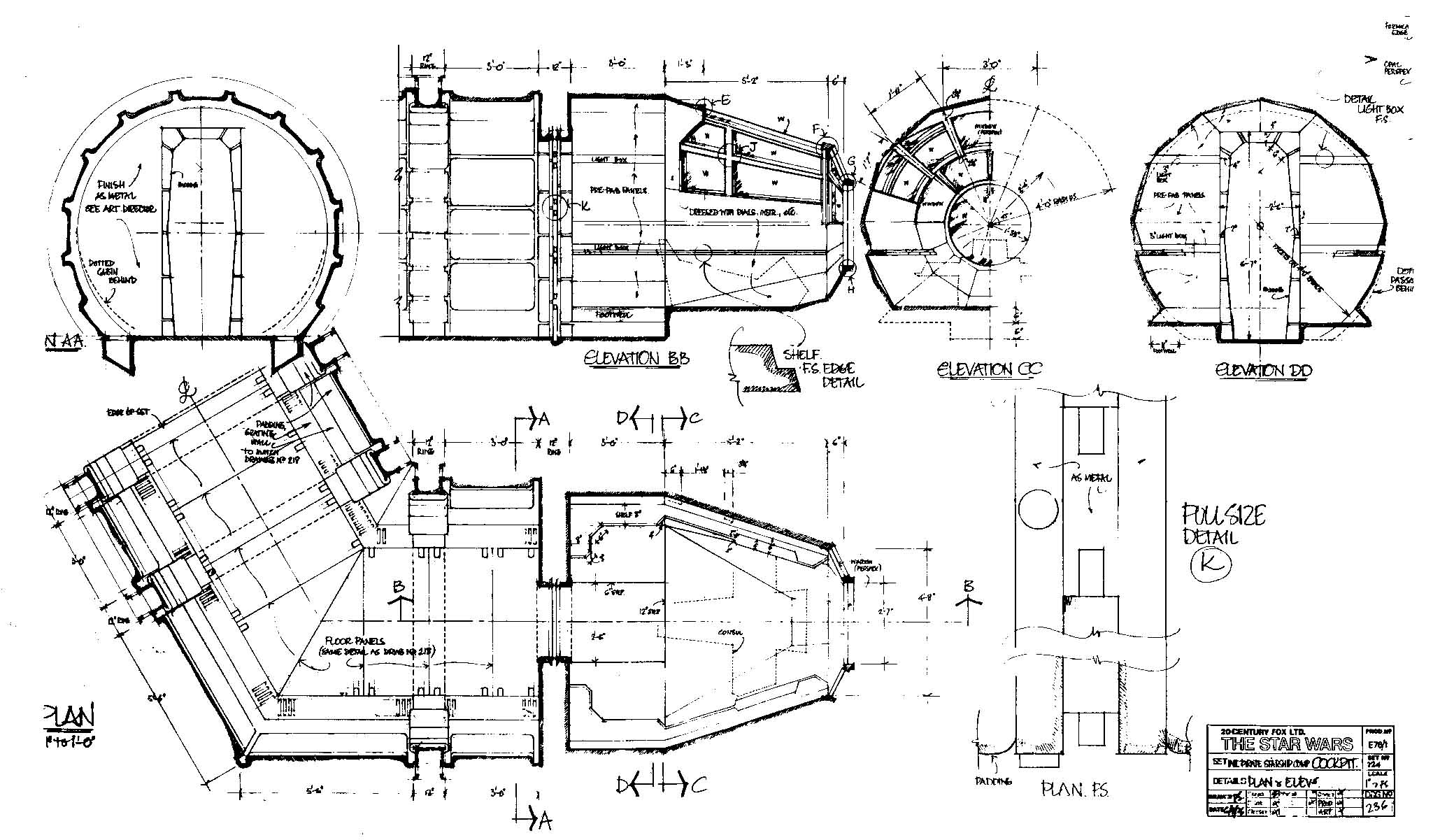

This was it. This was the Pirate Ship as intended for the screen. It got turned into a blueprint, which got sent to England, where the set was being constructed. Everything was ready to go.

Here is said blueprint, in which you can see the new engine block, with a main tapered engine centered amidst a cluster of boosters. Unfortunately only this sideview is available.

From Star Wars Blueprints.

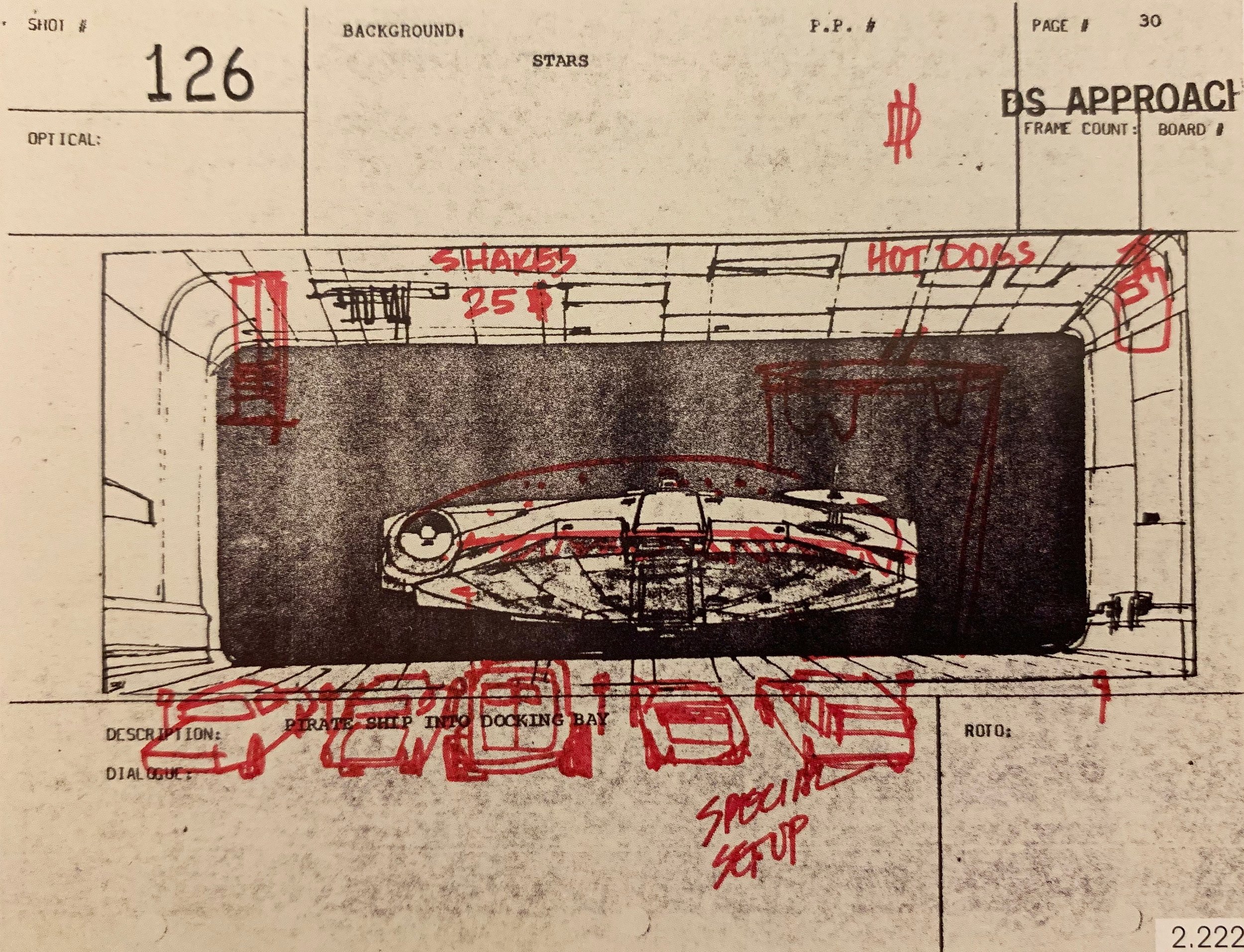

The Pirate Ship sitting in the Docking Bay in Mos Eisley

Cross-section escape pod blueprints

A variant of this new nacelle cluster would eventually end up on the Rebel Blockade Runner, and is one of the more iconic pieces from the vehicular design of Star Wars, yet this is the first time we really see it, so where did it come from?

Let me reiterate that the chronology of the development is at best educated guesswork, despite my best attempt at sourcing a timeline.

• • •

The following Cantwell model is a bit of an odd fish. A source told me that it was probably done late in 1975, and therefore is probably meant to be the Rebel Blockade Runner, not the Pirate Ship. J.W. Rinzler's language around this model in The Making of Star Wars (p169, iBooks) refers to it in a slightly ambiguous manner.

[...] an alternate Cantwell prototype had more rocket boosters, and those were incorporated into a later sketch by Johnston of the pirate ship [1] and into a painting by McQuarrie [2].

— The Making of Star Wars, p72.

1): Johnston's sketch follows McQuarrie's paintings below

2): McQuarrie's paintings w. rocket boosters follows these photos of Cantwell's model

Remarkably Lucasfilm rarely shows this thing off. It's hard to find proper photos of it and as far as I can tell it's only been at one exhibition (Celebration V, 2010) and is featured only in passing in Star Wars Chronicles and The Making of Star Wars (where the above photo is from, the rest are from Jason Eaton). It's also not featured at all on the blu-ray extras which otherwise do go through a lot of Cantwell's models.

Aside from the script-mandated “long” design, it's hard to see much of the final design springing from this. The nacelle cluster would end up being reconfigured from the X layout into a more rectangular one, the red spherical pods behind the cockpit module would become the escape pods, and Cantwell’s signature squashed hexagonal outline of the plates that intersect the hull seem to have made their way into the superstructure design of the next Cantwell model, the shape of which made its way into the ‘Blockade Runner’ design and arguably the Star Destroyer as well (as also indicated on Cantwell's unused concept art).

That model is definitely an oddity in the larger scheme of things, and I would love to know more about just how and when it came about, but for now we'll move on to the next stage.

The aforementioned source also told me that he had seen a drawing of the near-final Blockade Runner design with the X-like boosters instead of the rectangular configuration, although that has never surfaced anywhere, so I can't vouch for its existence.

Recall the first series of sketches by Ralph McQuarrie; while the Pirate Ship design was in flux, those same compositions were still the foundation upon which the film was built.

The following painting shows the Pirate Ship arriving at the prison facility, escorted by TIE fighters. To the uninitiated this looks a lot like Cloud City, but is in fact the imperial prison facility holding Princess Leia, from before it was combined with the Death Star (to save money and streamline the story).

The concept originates as so much else in Flash Gordon, although it's worth noting that Gulliver's Travels actually featured a floating city which could arguably also be considered the original inspiration.

As a callback to the 2001: A Space Odyssey connection, the craft taking off from the top of the facility always looked a lot like the Pan Am shuttle to me.

Even earlier prison concept, from inside Pirate Ship

McQuarrie finished the following painting on March 31st, 1975, about a half year after he first started on the production, showing the Pirate Ship in the prison facility hangar.

The first version of this production painting is clearly based on Colin Cantwell's model, of which McQuarrie had a photo he had taken, for reference.

McQuarrie's first attempt at the Pirate Ship, from Cantwell's model.

As noted in the phenomenal Star Wars Art: Ralph McQuarrie, where the above painting was first published (it remained unseen until late 2016), the escape pods which are rounded here, bear a striking semblance to the escape pods from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Soon however, the design of the Pirate Ship evolved into something a more toned down and with a distinctly more WWII aviation-like look, McQuarrie revisitied his painting, as he would do on many occasions.

From these sketches it looks like McQuarrie evaluated a couple of different shots with the updated design, but eventually, perhaps due to time constraints, nevertheless settled on the existing shot.

Now the film was beginning to gain its more realistic lived-in look and feel, and the ships finally began too look more and more like something out of Howard Hawks’s Air Force, with roots in the nuts and bolts aeronautics of the war, and brimming with heavy guns.

Ralph McQuarrie in his home studio, working on the pirate ship production painting (below), by Ed Summer.

At this stage the design of the Pirate Ship had been settled on. Based on McQuarrie's design Joe Johnston did the following drawing to hand over to the model shop which would build out the hero ship itself (referenced earlier in relation to the alternate Cantwell model).

According to J. W. Rinzler in The Making of Star Wars (p170, iBooks):

With Lucas's approval at each stage, John Dykstra drew additional sketches of the Pirate Ship, which Joe Johnston turned into more concept designs that Steve Gawley translated into orthographic drawings; then the Shourts and Grant McCune started construction.

Dykstra's sketches might have been of the ilk seen earlier, showing how a scene might be practically shot; at least I don't know of any other sketches of his that have survived so that's my best guess.

Right is a version of the above drawing which has the text "Concept/ Rebel Blockade Runner" above the “Approx 6’ long” note, seemingly in the same hand, presumably Joe Johnston's, but as far as I can tell that title was not part of the original drawing (it wasn't the Rebel Blockade Runner at the time). Also, the lines on that version look thicker, as if they have been copied possibly for the Star Wars Sketchbook, although I have not verified that it is in there.

Either way, the model was built largely to this very schematic, and includes both the familiar cockpit as well as the circular radar dish.

Click through to see the full images below.

Joe Johnston working on the pirate ship.

The ILM model shop, with Pirate Ship drawings on the walls and the first Pirate Ship in progress at the bottom.

Sidenote: A hobbyist by the name of Laurent Perini built a pretty boss model of Johnston's Pirate Ship sketch, and Stinson Lentz built a fantastic 3D model of the above, final Pirate Ship.

As the caption on the image above so rightly notes, what happened next is film history. The TV show Space 1999 began airing in 1975 and featured a recurring type of ship called The Eagle Transporter which at a glance looked somewhat like the Pirate Ship design. In fact, there's a photo seemingly taken at the exact 'oh shit' moment in ILM's model shop!

Yep, that's Space 1999's Eagle under the not-yet-painted Pirate Ship.

“The Eagle had a very NASA vibe to it, with a truss-like framework and modular panels. The Pirate Ship looked like something inspired by Jules Verne in space, but they both were long and relatively narrow with a cockpit at the front and clusters of engines at the rear. George insisted on a different look entirely, something that wouldn’t look like it had been inspired by anything we’d ever seen.”

Not wanting to be perceived as riding the coattails of a TV show—how very unworthy of the silver screen—was enough for Lucas to throw the Pirate Ship design under a bus, so as to not draw any unwanted parallels.

“They were all very upset that I changed the design, ’cause they had just finished building the other pirate starship,” Lucas says. “They had spent an enormous amount of money and time building that other ship, and I threw it out. It’s one of those decisions that was very costly, but I felt that we really needed the individuality and personality of a better ship.”

The exact cost of the first pirate ship is difficult to ascertain, because, according to McCune, “it got billed for everything,” but a rough estimate would be around $25,000—about a third of the total budget for the models. “It was seven feet long and had four hundred cycles of electronics going through it,” he says. So instead of scrapping it completely, that ship became the rebel ship, which was only in a couple of shots, while the vessel with more screen time was redesigned. “Joe, George, and John worked up this new idea for what they called the round ‘Porkburger,’ ” McCune laughs.”

This is where the story gets interesting, as well as somewhat confounding. First it seems like there was an attempt at retaining the Pirate Ship design by only altering parts of it.

This first stage sees the introduction of the hammerhead cockpit (literally two paint buckets flued together, covered in kit bashed parts), and what is referred to as the 'truss-like cockpit'. The earlier version was also taken to painting completion, as was this version as evidenced by the painting scheme detailing on the cockpit.

Although it's conjecture, it seems that at this point set construction had already begun in England and the budget and schedule was so tight that the Pirate Ship was forced to use the existing cockpit design.

So even if Lucas had deemed this a large enough deviation from The Eagle, the design would have to use the original cockpit design to fit the existing set

A technical illustration of the Blockade Runner by Joe Johnston.

Seen on the right us a technical illustration of the Blockade Runner by Joe Johnston. The details around this drawing are somewhat scarce, so whether it was actually done during production or afterwards is a little hard to pin down.

Remarkably the proportions aren't quite right, although the cockpit shows the final iteration of the model (as opposed to the above Pirate Ship variant).

Below is the final Blockade Runner filming model, AKA the Tantive IV, a name which is widely known, like many Star Wars names, yet never shows up in the films. The power of merchandising.

While this is the blockade runner configuration, I had to include this awesome photo of the model sitting in the model shop as the crew is working on a smaller version (used for the opening scene of the ship being sucked into the belly of the pursuing Star Destroyer).

Cockpit surgery in-progress

How the new Pirate Ship design evolves from here is somewhat vague and undefined. The timeline is an open question; whether the Blockade Runner was finished first, or if there was any intention of trying to use the first hammer-head design as the Falcon. These details are absent from the many behind-the-scenes sources.

What I look for in situations like this is missing links in the form of outside influences; the thing that causes the overall story to click and make sense. But in this narrative that missing link has yet to fully surface.

Covered up by the Dykstraflex.

Now we're going to try to figure out how the design went from the long Cantwell-esque design to the saucer-like Falcon design, the so-called ‘hamburger’, as we know and love it. We turn first to Lucas himself.

“The flying hamburger was my favorite design,” Lucas says. “I thought that the other design was too close to Space: 1999 and too conventional looking. I wanted something really off the wall, since it was the key ship in the movie; I wanted something with a lot more personality. I thought of the design on the airplane, flying back from London: a hamburger. I didn’t want it to be a flying saucer, but I wanted to have something with a radial shape that would be completely different from anything else.”

Case closed, right?

Well no, because as with so many quotes on the history of how these things came to be, this one too compresses the events, iterations and decisions into a sound-bite that is a little too straight forward. And in particular when concerning Lucas, it's important to take into consideration when exactly his interviews took place, as he has a tendency to clean up and streamline his stories over time. This particular interview might very well have been one of the followup interviews Rinzler did with him for the book in 2006, in which case it counts for much less than if it was from the 1974-80 era.

This isn't a quality only George Lucas has though. Here's Joe Johnston who created the new design, coming at this from a slightly different angle.

“The Pirate Ship was well under construction with many components of the model finished in great detail. George gave me the task of quickly designing a new ship, saying that the shape wasn’t important as long as it didn’t look anything like the ship from the TV show. The model shop had to stick to pretty much the same schedule of shooting that had been planned for the Pirate Ship. Grant McCune and his team were well aware that this model was going to have to come together very quickly.

I spent about a day doing a series of very rough sketches that soon evolved toward a disk-shaped hull with a long horizontal slot-shaped engine at the back instead of the traditional round nacelles seen on almost every other ship. Grant McCune asked if I could incorporate two elements from the old ship that had already been finished, the cockpit and the “radar” dish. The Blockade Runner was given the “Hammerhead” cockpit as a replacement.

I showed George the stack of sketches and we agreed on the general direction, with the offset cockpit and the raised “waistline” hexagonal structures, opposing gun ports and asymmetric details like the radar dish . Because of the time crunch there weren’t a lot of drawings done after this point, as the construction needed to get under way. I worked with the model builders to monitor the design as the ship began to take shape.

”

These are the sketches Joe Johnston made, exploring possible directions on this new ‘saucer’ concept.

These sketches were first made public in the summer of 2022 in the documentary Light & Magic, in which Joe Johnston also talks about the process of creating the Falcon. The sketches didn’t see the light for forty-five years after the film was released, and were added to this essay years after it was first published. Their once existence was all but certain, the silhouette of their contribution vaguely visible in the outline of a process which made some sudden jumps without any obvious work; to finally have them plugged into the narrative is very gratifying.

Even so, as it were, it wasn't quite as straightforward as Joe Johnston told the story above, but almost.

Firstly it's worth noting that there's a contingent of people who think that the inspiration for this stage of the design was drawn from the XB982 ship from the French comic Valérian and Laureline (covered in some detail in my essay on that subject).

In summary: it's certainly possible given that Joe Johnston was a fan of the artist; nevertheless I personally remain somewhat skeptical. The Valérian design is quite different, and just because you can put the two next to one another and have it look vaguely similar does not indicate actual inspiration.

Whatever the case may be, even if it did inspire the Falcon, it did so in a way where it might well boil down simply to the idea of having a 'saucer'-design. And once you've said saucer, well a hamburger isn't far behind.

Moreover, the hamburger notion might really have arisen not from someone binging at the local McD's, but from settling the idea of a saucer with the existing design language, as also seen in the Pirate Ship design; essentially two plates with greebly stuff in between them, as it had been since Cantwell's early sketches. It's distinctive in his early Star Destroyer paintings and the model itself, and it features prominently on the Pirate Ship model.

And if you were to talk about what a saucer might be expressed as in that language, it could be something like a burger; two plates with stuff mashed in between them.

“[George] may have said at some point that it could have the essence of flying saucer. I’m not sure about the conversation that happened almost forty years ago, but I do remember that it was a situation of “anything goes!” I started with identical upper and lower dish shapes that looked like they had been cut away around the edges to enclose components that had been hot-rodded together. Landing gear bays on the bottom and the com dish on the top helped to break up the symmetry and give it a distinct top and bottom.

I did several sketches with the cockpit centered, just above the loading arms, but I really liked the offset cockpit. It also let me add another asymmetrical tube shape that looked like it housed the corridor to the cockpit. Even though the ship is supposed to be a “spice freighter” I didn’t want the shape to give any indication of its purpose. It’s a big hot rod pure and simple.”

The missing link. A plan drawing of the intermediate step between the Pirate Ship and the Millennium Falcon. Finally printed in the 2018 art book for Solo.

In fact, the above plan drawings by Joe Johnston (which remained unreleased for 41 years, and which I literally had people who had seen it send me recreations of, but which I couldn't completely verify until it was finally released in the art book for Solo) the step-by-step approach the design process took is completely evident.

"What if we wrapped the hull with a saucer?" one can imagine them saying as they contemplated how to rescue the existing design without throwing the whole thing away. Drop the nacelle engines, file down a couple of edges and displace the cockpit, and you've got the final design.

So now we're really getting into it, we're beginning to clearly see each step of the process it took to land that final design, but just because it literally took me nearly ten years to get to this point, here is Joe Johnston in reply to a comment on the post he made about this article on whether the veracity of the 'burger with an olive on the side' story:

Before the above plan drawings were released, the only source I could find that hinted at the idea of the centered cockpit, a middle stage that seemed obvious, despite there being no evidence of it, was this sketch by Ralph McQuarrie showing the pirate ship arriving at the Death Star (same scene as the earlier ‘prison facility sequence’ moved to its new home).

The sketch is nearly rough enough that it could be interpreted any number of ways. Yet when I look at it, I see the saucer-like Falcon design, but with the cockpit mounted on the front, possibly with a little detail around the engine section, which would be where the nacelles were, which would mean this sketch was also made in the very short time span between the above plan drawings and the final design.

A study by McQuarrie based on green screen footage.

Star Wars design was all about primitive shapes (spheres, cylinders, squares, wedges), and a flying saucer isn't far out of reach when you're making a science fiction film.

If you were to intersect Cantwell’s Pirate Ship design with a saucer, it might in fact get you something that would create the outline in the above sketch.

Yet it was gone as soon as McQuarrie went to clean up the sketch prior to starting on the final painting, and he worked fast, so we could be looking at a change that literally happened overnight.

Here are McQuarrie’s four production paintings with the updated design, including the final version of the above sketch. Note that the cylindrical cross-section is absent in the sketch as well as in the final version, although whether that was purposeful or not is hard to say; at time production had to move fast, and some details were lost along the way.

This version of the Pirate Ship lacks the cylindrical cross-section behind the cockpit. It's possible that McQuarrie simply forgot to include it, and didn't have time to return to it (after all he didn't have time to return to paint in the surface detail on other Falcon paintings), but given that it is missing from the sketch as well, it could also indicate an in-progress redesign.

Here the cross-section is present. Also, note the two prongs jutting out from the mandibles; possibly some sort of canons, but could also play into the notion of the mandibles being where the cargo was supposed to go. This cockpit, by the way is a departure from the Cantwell-originated cockpit of the previous Pirate Ship.

McQuarrie's rearview also has the cross-section. Notice how the cross-section terminates before the discs (indented), versus the next painting, where it terminates outside the disc radius (outdented).

According to starwars.com "Ralph confided that this painting was actually unfinished. He was not intending for the edges of the Millennium falcon to be smooth, but never got around to incorporating the additional details." As a sidenote, it looks like R2 is leaving, but at the time he didn't roll, he walked! So that is him caught in mid-step, entering the hangar.

Now we're back in somewhat familiar territory, although how we got here is a bit hazy. Obviously a couple of things have occurred: a radically different saucer-like design has come into being and very possibly a short-lived version had a front-mounted cockpit.

What's going on?

The above sketch throws even more gravel into the machinery. The four previous paintings all seemed to agree more or less on the cockpit (glass on the upper side only), yet here's another in-progress variation.

It's possible that the version of the ship approaching the Death Star (the one without the cross-section) was an early version of a new design, which would make the the above drawing (which has the cross-section) an iteration on that design. I don't think that's the order of things though; I imagine the missing cross-section in the Death Star painting was a rare oversight on the part of McQuarrie.

Either way, this is my personal favorite design.

If I were to guess, I'd say that the curved glass cockpit was probably nixed because it would have been technically too hard to pull off the curved glass both in terms creating it, blue screening special effects as well as controlling reflections and lighting on set, which was probably why the final cockpit design, from Cantwell's first model, was ultimately chosen.

Moreover it's very possible that the cockpit was already in production in London, and so there was really no way around simply adopting it.

Adding to the mystery is this Joe Johnston storyboard which features the final saucer-design. Radar dish, cylindrical cross-section, except... no cockpit! Johnston however assured me that it was a simple oversight, in the heat of battle.

Heilemann is correct in his assumption about the storyboard with the missing cockpit. I just forgot to add it. There were far more egregious mistakes made in many of my other boards!

— Joe Johnston in reply to this piece.

There's another oddity from supplementary storyboard artist Gary Myers, whom Rinzler notes in Star Wars Storyboards, we know next to nothing about (which in itself is a crazy notion at this late stage of Star Wars fandom).

His version of the ship is similar to the final saucer-and-mandibles design, only it also lacks the side-car cockpit. Myers did storyboards showing the crew inside of a cockpit looking out, but it’s impossible to tell much about where on the ship it’s supposed to be.

To get some sense of the chronology of these boards, while the background behind the ship looks like clouds, and not stars, the notes on this storyboard peg them to take place on the Death Star (which means that a) it should be stars, and b) we’re none the wiser as to what came first).

Johnston's earlier storyboard.

On a sidenote, Rinzler pegs the artist of this first board as Johnston in The Making of Star Wars (p99), but in the later released Star Wars Storyboards: The Original Trilogy book has it as Gary Myers, which seems to make more sense.

In all likelihood the storyboard artist situation was vague at best before Rinzler really dove into it with the Storyboards book, and in the case of this particular board, it is actually a copy of an older board by Johnston (right), which featured the original Pirate Ship.

Myers rounded-edged style is so distinct that it's hard to imagine him having fed off of McQuarrie's obviously hard-edged (and cockpit-laden) versions below. But then when we look back at some of the comics that came out in the wake of the films, artists mis-remembering how spaceships looked wouldn't be that big a surprise after all.

I'd like to believe that somehow this mysterious Myers came in from the nowhere and dreamt up this completely different version of the Pirate Ship, only to then disappear back into thin air, but Joe Johnston himself helped me correct any such notion by addressing it directly.

Heilemann makes reference to storyboards that show a slightly different design. Storyboards were never used as design sketches. Each individual board artist was drawing his own version of the ships but the boards were not referred to by model builders for design details. Except in the very early stages of storyboarding, models were already built before the boards were drawn. Gary Myers did some excellent work on storyboarding several of the FX sequences, but he was not hired as a designer and to my knowledge didn't work outside the field of storyboarding, at least not on A NEW HOPE.

— Joe Johnston in reply to this piece.

Below are Joe Johnston's blueprints for the final Falcon, now named the Millennium Falcon (Johnston consistently, to this day, misspells it Millenium over Millennium). Worth noting here is that the new cockpit design is still here, but never made it to the model shop, which literally sawed the existing cockpit off of the old model and glued it onto the new one.

Technical illustration by Joe Johnston

The ILM model shop built the new Pirate Ship model, and quickly found a way to distinguish it from the old one in conversation, by adopting Grant McCune's nickname for it: The Pork Burger, probably because it was already being referred to as a hamburger-like design (Cantwell's plates and greebly as a saucer, remember?).

The above storyboard of the Falcon being pulled into the Death Star has been overdrawn by someone turning it into a weird mixture between a fast food counter and a drive in theater, calling back to American Graffiti and cementing forever the hamburger/Falcon relationship and

The model was used to create a set of schematics which were shipped off to England where principal photography was to take place at Elstree Studios. Supposedly, according to set designer Roger Christian, because of this the full-size Falcon has features that were really just remnants of glue on the original model, copied to the schematics.

You can almost make out in this blueprint, how the design evolved. The saucer retains the new angular cockpit, which was probably replaced right after these drawnings were made up, because construction in England on the old one had already commenced!

The illusion of the silver screen at its best; only half the ship was ever built for the first film.

Docking Bay 94 was one of the first scenes shot at Elstree. Only half of the Falcon was built. When shooting finished, the set around the ship was torn down only to be rebuilt as the Death Star.

The Death Star hangar bay was part matte painting (when our heroes glance down from above), but otherwise the same Falcon set.

I spy with my little eye proto-Jabba, Chewbacca, and on the far left, George Lucas.

Since Bogart was a source of inspiration for Han Solo, I always thought the name of the ship was somehow inspired by The Maltese Falcon (1941), or maybe from a source of inspiration for the soundtrack, The Sea Hawk (1940) in which the ship is named The Albatross. Birds all around.

I also noticed of course that The Eagle from Space 1999 was similarly a bird of prey, but it wasn’t until I ran across a reddit post that it clicked.

Add a year to Space 1999 and you get Space 2000, a new millennium.

The Millennium Falcon.

One of the interesting things about Star Wars is how the creative process so clearly wasn’t locked from the beginning. It was a long and winding road, and throughout writing the essays for Kitbashed I’ve found that despite intense pressure there was always an energetic adventurousness with ideas which inevitably lead to some of the most iconic designs in film history.

The Falcon is a great example of that, specifically because the final design is so distinct. It makes it a much more enticing to try to decipher how it came about.

While I’ve been pursuing this subject for years, it wasn’t until I starting putting together this essay that I finally began to find some of the finer details of the Falcon’s creation.

Ralph McQuarrie’s sketches in particular were something of a revelation for me; I’d forgotten that he had done those early Pirate Ship sketches, and I’d never even considered the very first sketches he did as portraying the Pirate Ship (nor has anyone else as far as I can tell).

It’s also just a pleasure to revisit McQuarrie’s Star Wars, which is quite a bit different from what ended up on the screen. As much as I love the used-universe of the final film, I also appreciate why Lucas would have found the film to be somewhat disappointing when compared to what McQuarrie had put in his head. His use of color, light, shapes and space is unparalleled. Even his sketches brim with life and potential.

• • •

There are still a lot of vague and unanswered questions in the exact design progression (I've done my best to recreate it, but it is an attempt fraught with missteps), but I will come back and slowly fill in the last missing pieces over time.

Unfortunately Joe Johnston’s mythical missing link-‘centered cockpit’ sketches have not been released over the years. It would certainly fill in a blank on our map, even as the saucer design process is beginning to come into focus for me, and hopefully for you the reader as well.

But I've been assured by two separate sources that the drawings do still exist, but are in private hands, so there is hope yet. It is likely that they will end up on auction, when that private owner's grandchildren need to go to college; it's played out like that several times in the past anyway.

At least I feel like I finally managed to largely dispel the burger creation myth, which has haunted me for years.

I leave you with these stills from the final film, and hopefully a feeling that you now know more about the Millennium Falcon than you ever wanted to; maybe it’ll come in handy at some trivia night down the road.

We're not quite done yet.

The Falcon underwent a significant change from A New Hope to its reappearance The Empire Strikes Back. The original design has three landing gears, two on the rear of the saucer and one at the front, in the middle.

That fueling pipe is all that's holding her up

These special modifications however caused the ship to be unbalanced, which was fixed in the original sets for Docking Bay 94 and the Death Star hangar (same Falcon, different set) by having a fueling tube cover up a metal rod which was in reality propping up the ship to avoid having it tip over! It's the one Han Solo steps away from when he first greets his passengers just before takeoff.

For Empire however, this had to be fixed, so two box-like structures were added on either side of the saucer on both the 5-foot and the 32-inch models that had been used on A New Hope, and the landed Falcon gained two extra landing gears for a total of five.

The mandibles also gained headlights, although I'll leave it up to the reader to investigate that on their own.

The A New Hope version of the Falcon had only a single landing gear on the front, center hull.

Michael Fulmer working on the new landing gear for the Empire Strikes Back Falcon. Notice the new boxes on the front.

Selwyn Eddy overseeing the landing sequence in Empire Strikes Back, with the new landing gear in place.

The ESB Falcon undercarriage with all the new boxes for the retracted landing gear in place.

This article would not have been possible without the help of many people and existing sources. I would be remiss if I didn't highlight in particular the Star Wars Rare Vintage Photos group on Facebook, which is a unique treasure trove from which I have plundered many of the photos used here.