1:42.08 (1966)

A clear precursor to THX 1138's car chase, this short features a car doing laps on a track. Trademark early-Lucas photography and tone poem-esqueness.

Torn out of his days cruising the streets of Modesto, American Graffiti is Lucas's love letter to a long since dead mating ritual. Seeming perhaps a sidestep in relation to Star Wars, when compared to the science fiction worlds of THX 1138, it was crucial in shaping the populist approach with which Star Wars conquered the world.

Lucas, who veered towards ‘purist’ cinema, found more success than he ever dreamed of, when he heeded the advice of his mentor Francis Ford Coppola who suggested he try ‘a regular movie, perhaps a comedy’.

Film critics at home with Godard and Kubrick received THX 1138 with open arms. But the public was a lot less receptive to the cold, alienating sci-fi film. In an attempt to salvage what they could from what they perceived as a disaster, Warner Brothers had tried ‘putting the freaks up front’ by opening with the climactic chase sequence. It didn’t nudge the box office, but it fueled the young filmmaker’s disdain of the studio system even further.

As with many director/producers, Lucas’s oeuvre can be considered to consist either of the films he himself directed (starting with THX 1138, a grand total of six) — the puritanical approach — or it can envelop all of, or at least many of the films he has been involved with as a producer as well. The latter seems preferable, given that both The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi as well as the Indiana Jones series would otherwise disqualify, and while they bear the marks of their respective directors, they are undeniably Lucasian.

Regardless of how the cake is sliced, American Graffiti is the odd man out. Neither science fiction, nor particularly adventurous, it swings the pendulum from one extreme — the exotic and alien world of THX 1138 — to another — the conventional and nostalgic world of Lucas’s hometown, Modesto. Out with the silver faced robots and dystopian society, in with the rollerskating fast food waitresses and cruising teenagers; clearly a reactionary move to the cold reception of THX 1138 and Francis Ford Coppola’s suggestion that he try doing a ‘regular movie, perhaps a comedy’.

The original poster for I Vitelloni, showing the film's main character and his friends, doing what they do; hanging out.

Shot on a shoe string budget over the course of a month, a cut-throat schedule for any film, let alone one shot mostly at night, American Graffiti wasn’t like anything else out there: An American mating ritual crossbred with a fragmentary european sensibility, driven by a ceaseless rock n’ roll soundtrack true to the period.

Ostensibly a time capsule of Lucas’s teenage years cruising around Modesto, the inspiration for making it in the first place had, according to Lucas, come from Frederico Fellini’s I Vitelloni (1953), a film about “the pleasures and frustrations of growing up in a provincial town”[1], which had very distinct autobiographical elements of Fellini’s own life. While the film itself is far from Graffiti’s rock-and-roll soundtrack, neon lights and fast food joints, it nonetheless has the same air of pranks, camaraderie and aimless wandering that also runs throughout Lucas’s film.

The original poster for Peter Bogdanovich's The Last Picture Show (1971).

Underlining American Graffiti’s connection to the more artistically recognized Italian neo-realism, he noted in the March 1973 edition of Seventeen Magazine on that inscrutable title of his:

“Graffiti is an Italian word, meaning any drawing or inscription on walls, glib, funny, immediate.”

"I'd always liked the idea of Fellini's film I Vitelloni, which is kind of the same issue about growing, and about taking responsibility and moving out of the house and that whole trauma. And it was one of the themes that was in my first film, THX, and I wanted to expand on it". [2]

Another film which shares many similarities with both Fellini's film, as well as with American Graffiti is Orson Welles protégé Peter Bogdanovich's first film, The Last Picture Show, which premiered the year after THX 1138 was released, to rave reviews and no less than eight Oscar nominations, including Best Director (it took home two, in the supporting acting categories).

Set in a small Texan town in the early 1950s, it's a coming of age story of two friends (Timothy Bottoms and Jeff Bridges), which takes place over the course of a year and follows the two through a variety of situations. Timothy Bottoms's character ends up eloping with (first-timer) Cybil Sheperd's character, and Jeff Bridges’s character enlists and ships out for Korea. While it is tonally much more mature than Graffiti, its release-timing, focus on youth-culture, small-town setting and an almost wall-to-wall soundtrack of 1950s rock and roll, makes it a shoe-in as an impetus for American Graffiti. They even share the fact that they both hang a lot of their nostalgia on the imagery of youth-institutions of their respective times. The cinema in The Last Picture Show (which opens and closes the film), and Mels Drive-In in American Graffiti, which embodies the style of the film. And while the film was based on a 1966 auto-biographical book by Larry McMurtry, it also shares many similarities with I Vitelloni, including having been shot black-and-white, a rare choice at the time.

Both The Last Picture Show and I Vitelloni share the biographical nature of American Graffiti, as well as the youth-culture focused, and in the case of The Last Picture Show, often car-centric lives of its primaries.

Wanderlust. Escape. Leaving the comfort of what Joseph Campbell called the ordinary world, is easily the most common refrain running throughout all of what might be considered Lucas’s main canon, right from his earliest student films, up through THX 1138 and American Graffiti and into Star Wars. Be it to leave the horrors (or confining doldrums, as is the case with THX) of fascism, or simply to seek out adventure and to explore. It’s an image perhaps never captured on film quite as poetically as when Luke’s wistful stares off into the horizon, at the setting suns of Tatooine with John Williams’s orchestral magic rising on the soundtrack. It is however also a thread running throughout American Graffiti’s interweaving stories, as the main characters each try to figure out what lies in their respective futures; whether to leave or stay.

Where THX 1138 ended on a note of cautious optimism with a sense that the adventures and sacrifices of its unlikely hero hadn’t been for nothing, it’s hard to say exactly where American Graffiti stands on the issue of leaving home. As Curt’s plane takes off and leaves Modesto behind, he peers out the window and spots on the road below him what is undoubtedly the white Ford Thunderbird he’d been chasing all night; his dream girl. The car is driving in the same direction as the plane is flying, yet out of reach. Did he leave behind the love of his life? Is she going with him? Was it worth it? The post script makes no mention of it.

“Everybody has a different way of checking out a culture. Some look at clothing, others study cars. My way is to examine rock radio, which is an American form of graffiti. And there’s a strong relationship between listening to the radio and cruising around a car on a hot summer night; you always went hoping to meet the ultimate girl but you never did. Ten years ago, when I was eighteen in Modesto, California, it was the largest city within forty miles, big enough to have two high schools, so you didn’t know everybody and the only way you could meet girls was the cruise around all night. There were at least a thousand kids who came from all over the valley, from San Francisco, Stockton, Sacramento. We had wall-to-wall cars! You’d park your car and ride around with other guys. I spent most of my money on gas. In the sixties, the social structure in high school was so rigid that it didn’t really lend itself to meeting new people. You had the football crowd and the government crowd and the society-country club crowd and the hoods that hung out over at the hamburger stand. You were in a clique and that was it; you couldn’t go up and you couldn’t go down. But once you got on the streets it was everyone for himself and cars became the way of structuring the situation. If you had one, it gave you a new position. You didn’t have to be president of the class or the toughest guy around; you could just have the neatest car! In your teens, if you really get into something it becomes all important, like your life’s blood. I spent three years of my life driving around in circles and didn’t get anything accomplished but I don’t consider the time wasted. This movie makes use of a lot of things that happened to me. [3]

It’s an interesting unresolved aspect of Lucas’s personality that his most personal films all at their core have this tremendous yearning for the great unknown, yet the man himself is perhaps the biggest homebody since Stanley Kubrick. It was undoubtedly a frustrating experience for him to grow up in the backwaters of Modesto in the 1950s, where the adventures of Flash Gordon and Zorro only fanned these flames into a roaring fire. He left Modesto for USC of course, and with the production of Star Wars travelled to both England and Tunesia, as he would do with Raiders of the Lost Ark. Yet by the time the production of The Empire Strikes Back rolled around he didn’t go to Norway for the filming of the Hoth scenes, and for Return of the Jedi it almost seems as if the script was deliberately written to allow it to be filmed in the backyard of Skywalker Ranch (most of it within less than a day’s drive from it in fact). A ranch Lucas had built specifically to allow for him and his to imitate the best qualities of his time at USC. The Ranch of course is just outside San Francisco. Two hours drive from Modesto…

It’s an almost ridiculous simplification of course, but nonetheless, this is the man who dreamt of running away? Of underground computer-controlled cities and a vast galaxy of aliens locked in interstellar war? This tension between nostalgia and the safe comfort of the known world, be it in northern California. or the heroic exploits of western heroes, WWII pilots and swashbuckling spacemen, and the exotic mysteries of space and the orient seems irreconcilable. Yet it is arguably the heart and soul of his best, most personal work.

At a more tangible level, Lucas’s love of cars is naturally at the forefront of the film, echoing images and ideas harking back to his student films Herbie and 1:42:08, including of course The Emperor. In fact Lucas had initially wanted to make The Emperor about Wolfman Jack, but at the time simply didn’t know how to get to him. Luckily when it came time to roll cameras on Graffiti, the real Wolfman Jack had come out of hiding.

Starting with OMM in THX 1138, the omni-present Jesus-like idol through whom THX and his fellow man search for absolution and consolation, only to be met with pre-recorded bits of sympathy, the god/father-figure motif is one Lucas would return to again and again. In THX 1138, as the carefully constructed facade of the world starts to fall away, the bureaucratic SEN stumbles upon an empty television studio that turns out to be where the fake messiah is broadcast from (a 1960s counter-cultural sentiment if ever there was one… man). It’s a scene mirrored in American Graffiti when Curt stumbles upon a seemingly empty radio station. A man appears, whom he at first believes to be Wolfman Jack, an idea quickly dispelled when the man reveals Wolfman Jack’s shows as nothing more than mere tape recordings; the rambunctious shenanigans of Wolfman Jack turn out to be as fake as the consolation afforded by OMM, crushing the very idea that there was ever interplay between the Graffiti kids and their idol.

Until that is, Curt on his way out of the radio station turns around one final time, and seeing that the man was Wolfman Jack after all (and that he keeps his promise of using his god-like powers to put Curt in touch with his dream girl).

It’s a noteworthy turn. Similar in a sense to the way in which Electronic Labyrinth broke from the hopelessness of Freiheit by allowing THX a chance to make a life for himself in the outside world, where Freheit offered only death for the man on the run, it shows a distinct change of course. It could be reading too much into a simple nudge-nudge, wink-wink to say that this was the first sign that Lucas had started rediscovering his spiritual side, but considering that THX 1138 all but says out loud that God is a lie and Star Wars virtually brims with spirituality, the stepping stone ‘he isn’t, but he is’-reveal of the real Wolfman Jack as an admission of: “Okay, maybe there is… something,” suddenly doesn’t seem so far-fetched. At least it’s an acknowledgement that not all authority is repressive and antagonistic, clearly a sign that the 60s were starting to wear off.

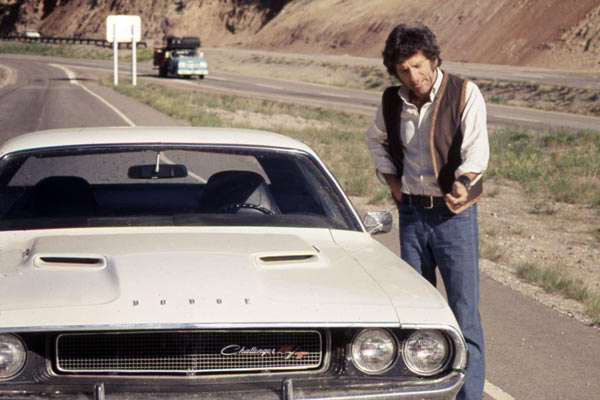

The 1970’s were replete with car-centric films, something Lucas no doubt loved, being a huge car enthusiast. 1971 alone saw the release of William Friedkin’s runaway hit The French Connection, Spielberg’s Duel, the Gary Kurtz-produced, Monte Hellman-directed Two-Lane Blacktop and of course Richard Sarafian’s existentialist road movie Vanishing Point.

Vanishing Point sees a former race car driver named Kowalski (Barry Newman) high tailing it across the American west with the police in hot pursuit, aided by radio station DJ Super Soul (Cleavon Little), who acts as a kind of greek choir to Kowalski’s suicidal run through the desert.

Kowalski's a essentially a smuggler, and even shares dressing habits with another certain smuggler.

Not only does Kowalski sports a white shirt and black vest for the first half of the movie, not unlike that of a certain other blockade runner, but it features an ever-present radio blasting a rock ‘n’ roll soundtrack, which could very well have been the seed for Lucas’s approach to American Graffiti’s famous score.

Much of Vanishing Point seems in turn to have been inspired by that icon of the New Hollywood movement, Easy Rider, released in 1969 and which featured a not dissimilar structured story about the road, freedom, the American dream and of course drugs. In fact, several of the picaresque encounters in Vanishing Point seem cut almost straight out of Easy Rider, a movie which famously also overflowed with rock ’n’ roll.

As a sidenote on the use of sound, and in particular a rock'n'roll soundtrack, something that didn't see widespread use until the late 1960s and early 1970s, it just so happens that American Graffiti's editor and sound designer, Walter Murch would go on to work on a re-release of Touch of Evil (1958) in 1998, all from the 58-page memo Orson Welles had written to Universal when he was originally ousted from the editing room[4]:

“What was astonishing to me, was that [worldizing (recording sound and music so it sounds like it belongs in the scene, rather than on the soundtrack)] was something I thought I’d invented for film in the late sixties, and which I’d used extensively for a number of films, up to—and especially including—American Graffiti. But here Welles had already done it ten years earlier in 1958.”

The ‘real-world’ feel of American Graffiti's soundtrack was in fact something Welles had very specifically precursored in his notes:

This rock and roll comes from radio loudspeakers, juke boxes and in particular, the radio in the motel.

It is very important to note that in the recording of all these numbers—which are supposed to be heard through street loudspeakers—that the effect should be just exactly as bad as that. The music itself should be skillfully played, but it will not be enough in doing the final sound mixing to run this track through an echo chamber with a certain amount of filter.

To get the effect we’re looking for, it is absolutely vital that this music be played through a cheap horn in the alley outside the sound building. After this is recorded, it can be then loused up even further by the basic process of re-recording with a tinny exterior horn…. And since it does not represent very much in the way of money, I feel justified in insisting upon this, as the result will really be worth it.”

Finally, the pre-credits cards detailing the further adventures of American Graffiti's main characters is straight out of The French Connection, where instead of detailing the main characters, they underscore the bleakness of the films story with details on the often limited sentences given to the bad guys after they were rounded up at the end of the film. The very kind of lifted-finger-hopelessness THX 1138 had stood for, and which Star Wars would turn to combat.

THX 1138 had been almost devoid of proper human relationships, yet they are ubiquitous in Graffiti, which in turn, much like THX 1138 seems almost devoid of traditional narrative structure, favoring instead an almost channel-surfing manner of storytelling (it’s a broadcast term kids, ask your parents). Star Wars in turn is structured in a much more traditional manner than both of its predecessors, Lucas did make an attempt at bringing over the more organic relationships he had built Graffiti around, though the most Graffiti-esque scenes in which Luke goes to Anchorhead to tell his friends about a space battle he had seen, were ultimately excised from the final cut(s) of the film to speed up the pacing.

Though there is plot-wise little connective tissue, another carry-over from THX 1138, which resurfaces again in Star Wars’s climactic space battle, is the race scene and of course vis-á-vis Star Wars, the accompanying Harrison Ford. Discussions on the continued care-taking of his films aside, Lucas is nothing if not consistent.

Inevitably the studio’s meddling did little to stop the film from becoming an overnight success and going on to become, to this day, the best cost-to-profit movie ever made, earning Lucas the means, and the clout, to start building his space adventure.

Lucas was right; the establishment wrong. A lesson which would drive him to fight fiercely for independence for the rest of his life.

Alpert, Hollis (1988). Fellini: A Life. New York: Paragon House.

Interview with George Lucas. October, 2009. American Film Institute.

On Location by Edwin Miller. March 1973. Seventeen Magazine.

The Sounds of Evil by Tim Tully. Accessed October 18, 2015.