Anyone Lived in a Pretty (How) Town (1967)

A photographer walks around a small town, and as he takes pictures of its inhabitants, they disappear. Shot in widescreen and color, a technically impressive short, albeit somewhat uninteresting.

As a part of a promotional effort by Columbia Pictures, Lucas spent weeks in the desert shooting a 'behind the scenes' short for McKenna's Gold.

Fresh out of USC, Lucas would witness first-hand the bloated, ailing studio system at work.

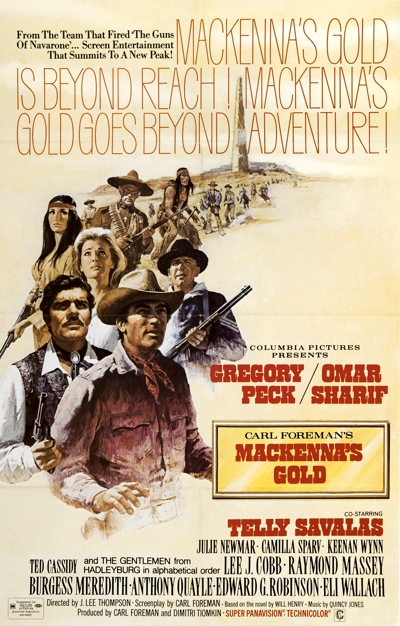

The theatrical poster for McKenna's Gold

In the summer of 1967, off the back of the success of Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB, his final effort at USC, Lucas won a scholarship from Colombia Pictures= to shoot a promotional short for a new treasure-hunt western starring Gregory Peck and Omar Shariff, from Guns of Navarone producer George Foreman, who also co-sponsored the initiative, and director J. Lee Thompson, MacKenna's Gold.

The studio system was on the cusp of the revolution that would begin to unravel it, a revolution led by the very students Columbia Pictures were wooing. Students that often had little more than scorn for the aging Hollywood machinery and their massive, lumbering productions. Says Lucas:

“We had never been around such opulence, zillions of dollars being spent every five minutes on this huge, unwieldy thing. It was mind-boggling to us because we had been making films for three hundred dollars, and seeing this incredible waste-that was the worst of Hollywood.”[k1096, 1]

Despite his film student snobbishness, at least according to his wife at the time, Marcia, “George wanted to direct. One of the reasons he did the Foreman project was the learn about directing and hopefully to make an impression on Foreman.”[k1076, 1]

Lucas, ca 23yo with Carl Foreman (left) and Gregory Peck (right) on location in Utah or Arizona in 1967.

Foreman was a legend in Hollywood, with producing credits on such distinct films as High Noon, The Bridge on the River Kwai and together with MacKenna’s Gold director J. Lee Thompson, The Guns of Navarone, a Lucas favorite which would go on to inform several key points in the first Star Wars film, in particular the planet-destroying weapon which ended up in the Death Star.

The scholarship was given to four film students, Lucas was joined by Charles Braverman (Portrait of a film-maker : Carl Foreman) also from USC as well as two UCLA students, David MacDougall (dir. J. Lee Thompson : director) and J. David Wyles (dir. Mackenna's Wranglers), each of whom set out to create their own short, portraying some part of the making of the film on location in the sweltering desert heat of Utah and Arizona.

Of the four films, Lucas’s short stood out as the only one that paid little heed to the actual production; almost disdainfully so in fact. A series of desert impressions; a tone poem of the sort Lucas had loved since he’d started at USC. Electrical poles. Flowers. Shimmering heat. It used some of the same aesthetic techniques Lucas had used on 1:42.08; deep focus and long shots; early favorites of his.

A daring film in the sense that it went against the nature of the assignment, which of course had been to provide MacKenna’s Gold with some marketing material. And remarkable in that it somehow manages to communicate the very thing Lucas learned on the shoot however, namely that Hollywood was in deeper trouble than he had first thought.

The film, which falls in line with Lucas's Lipsettian love of numbers, was titled from the day it was finished, June 18, 1967: 6–18–67.

The PBS outlet in Los Angeles did a special about the project [red. it was called After film school—what?, directed by ‘Mossman’, produced under Highroad Pictures, Inc and aired on KCET October 20, 1967. It was hosted by Charles Champlin who later authored George Lucas and The Creative Impulse, where this quote is from], featuring Foreman, the four filmmakers, and their films. Foreman at first opposed Lucas’s film, the subsequently honored “6.18.67,” on the grounds that it had nothing to do with the feature itself. … It was clearly the most innovative and original of the four films, as Foreman ultimately and privately agreed.[p19, 2]

The experience solidified Lucas’s resolve to stay away from the system; to make it on his own, or not make it at all. It may also however have left another mark; while it's merely conjecture, a good case could be made that Lucas might well have drawn inspiration from McKenna's Gold in the creation of his other big franchise, about a treasure hunting archeologist looking for a lost ark.

Dale Pollock. Skywalking: The Life And Films Of George Lucas, Updated Edition (1999). Kindle Edition.

Charles Champlin, George Lucas: The Creative Impulse.