In this six-part series, Birth of a Hero, we span a hundred years of science and science fiction to What does an Italian astronomer and a rich, eccentric American from the turn of the previous century have to do with fantasy and space opera? How many times can an officer go to Mars before the public takes notice? What does any of this have to do withStar Wars?

Lucas’s love of the serials and comic book adventures the likes of Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon stretches back much further than his work on Star Wars. Indeed his first theatrical feature THX 1138 opens with a preview segment for a Buck Rogers episode.

GL: The “Flash Gordon” strip was in our local newspaper and I followed it. In the comic book area I liked adventures in outer space, particularly “Tommy Tomorrow” but movie serials were the real stand-out event. I especially loved the “Flash Gordon” serials. Thinking back on what I really enjoyed as a kid, it was those serials, that bizarre way of looking at things. Of course I realize now how crude and badly done they were.

AA: Do you think the enjoyment you got from those serials led you eventually to make the Star Wars pictures?

GL: Well, loving them that much when they were so awful, I began to wonder what would happen if they were done really well. Surely, kids would love them even more.[kl383, 1]

At some point during the 1973 post-production and release of his second theatrical feature, American Graffiti, he started playing around with the idea of making an actual Flash Gordon-esque space adventure. Of all the sources of inspiration Star Wars is beholden to, Flash Gordon is undoubtedly the most famous.

“I tried to buy the rights to Flash Gordon. I’d been toying with the idea, and that’s when I went, on a whim, to King Features. But I couldn’t get the rights to it. They said they wanted Frederico Fellini to direct it, and they wanted 80 percent of the gross, so I said forget it. I could never make any kind of studio deal with that.” [p4, 7]

According to Lucas’s biographer, Dale Pollock, Fellini himself had actually optioned the rights[k1549, 2] from King Features. When exactly, and under what circumstances, or if it’s actual fact or simply misinterpretation of Lucas’s oft-told story, is hard to say. And the sensuous, art-centric Fellini might at first seems like an odd choice for something as frivolous and indeed American, as Flash Gordon, but there is meaning behind the madness, as Fellini explains in his 1976 book, Fellini on Fellini:

It is very hard to explain just how much the coming of Alexander Raymond’s Flash Gordon meant to boys of my generation in Italy. When we began to read about the astounding adventures of this galactic hero, fascism was at its height, its gloomy, dreary rhetoric in full flood. Admittedly fascism kept calling us to bravery and daring, kept telling us the need to fight and win, but what it said seemed boring rubbish, and the heroes it set before us were not the least bit attractive. Flash Gordon, on the other hand, seemed an unbeatable hero from the very beginning, a hero who belonged to real life even though his actions took place in distant, fantastic worlds.

I, and others of my age, have remained deeply attached to Flash Gordon and his creator. When I think of him, I think of someone who really existed. At times in my films I have wished to use the colours which the Italian newspaper used in printing the Flash Gordon strips.[p140, 3]

With the rise of European fascism in the 30s, the culture clash between the old and new worlds came to a head. In november of 1938, at the orders of Mussolini, the Ministry of Popular Culture put down a ban on most American comic books (excepting some, such as one of Mussolini’s favorites: Popeye). Unfettered, Fellini once told journalist Francis Lecassin, the he had set about writing a bootleg sequel to Raymond’s Flash Gordon. According to Fellini, he simply extrapolated from the existing story, though Leonardo Gori has doubts that Fellini’s bootleg-story is true, since it has seemingly no evidence to support it. And Nerbini, the company Fellini worked for, didn’t publish any sequels to Flash Gordon until 1944–45.

It remains unresolved, as does what a Fellini-directed Flash Gordon film might have looked like. Lucas meanwhile remained unfazed.

“[…] Flash Gordon is like anything you do that is established. That is, you start out being faithful to the original material, but eventually it gets in the way of creativity. I realized that Flash Gordon wasn’t the movie I wanted to do; if I had done it, I would’ve had to have Ming the Merciless in it — and I didn’t want to have Ming the Merciless. I decided at that point to do something more original. I knew I could do something totally new. I wanted to take ancient mythological motifs and update them – I wanted to have something totally free and fun, the way I remembered space fantasy.”[p4, 7]

I realized that I could make up a character as easily as Alex Raymond, who took his character from Edgar Rice Burroughs. It’s your basic superhero in outer space. I realized that what I really wanted to do was a contemporary action fantasy. [Lucas, p43, 7]

So, to tell the story of Star Wars, we must start by telling the story of Flash Gordon. It’s the story of a character from a more innocent time. Before Vietnam or Watergate, even before World War II. It’s a story that’ll take us back through the evolution of science fiction over the course of a hundred years, and our journey starts with a young illustrator by the name of Alex Raymond.

Born in La Rochelle, New York in 1909, the eldest of seven children, Alex Raymond was a largely self-taught artist, with only one art class under his belt. At the very beginning of his career he had worked as an assistant on Tillie the Toiler, Tim Tyler’s Luck and Blondie. Driven and ambitious, and already remarkable at anatomy and human poses, he got his shot when King Features decided to go head to head with the extremely popular Buck Rogers comic strip, the first science fiction strip to receive any kind of attention from the general public. Based off of the writings of Philip Francis Nowlan, who had started the character, Anthony Rogers, in his first novel, Armageddon 2419 A.D., it had debuted in 1929 to a world enthralled with the wonders of science; perfect timing.

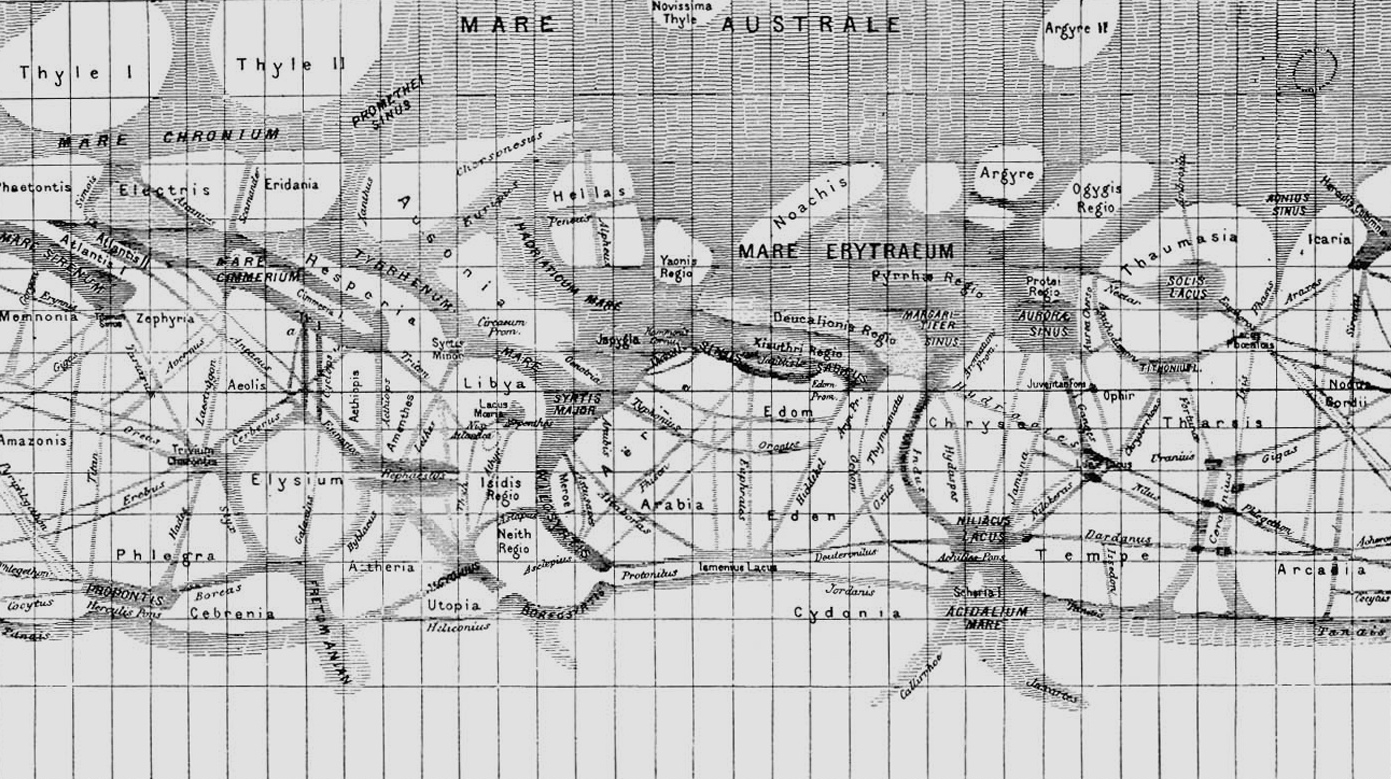

After a few years on the back of the newspapers, Buck Rogers had grown to become the most widely read comic strip in America. Seeing this popularity, King Features decided to get onboard the science fiction train, and the young Alex Raymond was paired with writer Don Moore to come up with something that could rival Buck Rogers. What Raymond and Moore created did away with the science-centric approach of Buck Rogers in favor of a much more fantasy-like setting. Dragons, shark-men and gleaming castles were as prevalent as spaceships and laser pistols on the planet Mongo where the stories predominantly took place. Where the novelty of science was often at the center of Buck Rogers, Flash Gordon was characterized more by Flash’s courage and the fantastic creatures and situations on Mongo.

There is some disagreement as to who exactly came up with the premise for Flash Gordon. Raymond himself claimed that he worked on it alone for a time, whereas Don Moore claims that he in fact was onboard as the writer from the beginning. Whatever the case, its basic premise is very similar indeed to that of Buck Rogers. An Earth-man transported, not into the future as was the case with Buck, but into space, to the planet Mongo, just as an alien planet hurtles towards Earth, threatening to destroy it. A scenario straight out of the novel When Worlds Collide, which had premiered in 1933, the year work on the strip had started (When Worlds Collide was later turned into film in 1951).

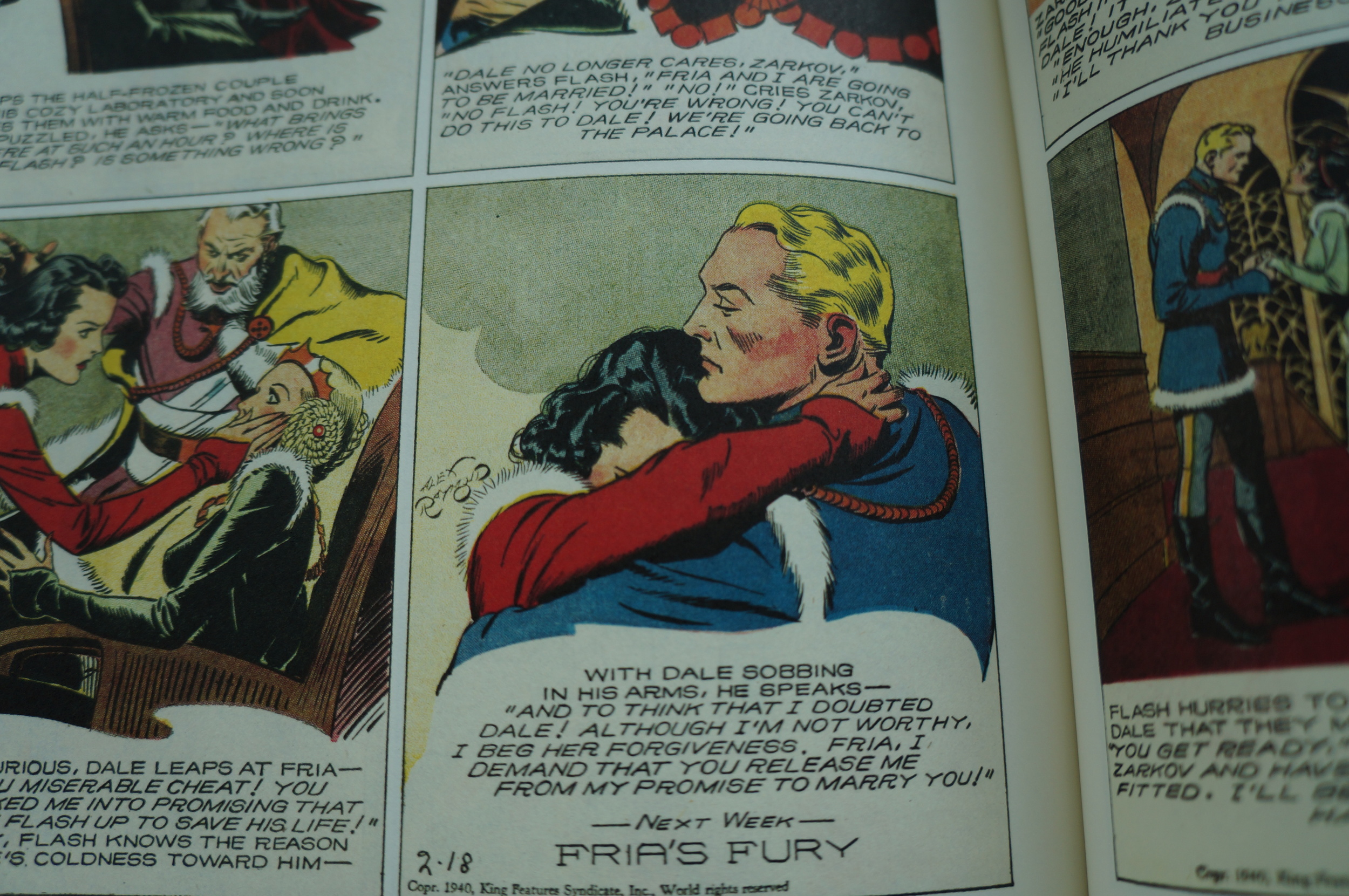

And rival it, it did. First published in 1934, Flash Gordon as the new character was named, quickly became the single most popular comic strip in the history of the medium. It may seem strange today, but so popular was it at the time, that people would buy the newspaper for the comic strip alone. Fueled both by the rip-roaring story of Flash fighting off the hordes of the evil emperor Ming and over the years gathering the peoples of Mongo to march against him. Each strip would leave Flash and his friends facing certain doom from monsters, sword-wielding foes, and pits of doom. Inevitably solved by the first or second panel of the following strip, leaving just enough room to rinse and repeat.

Raymond, who until the debut of Flash Gordon had been an unknown soon rose to fame and glory thanks to his dazzling artwork which lit the imagination of people everywhere. It was a transformative experience for Raymond, who took to the art of comics as a fish to water.

“I decided honestly,” he says, “that comic-artwork is an art form in itself, it reflects the life and times more accurately and actually is more artistic than magazine illustration—since it is entirely creative. An illustrator works with camera and models; a comic artist begins with a white sheet of paper and dreams up his whole business—he is playwright, director, editor and artist at once.”[4]

A few years into the run of Flash Gordon, war broke out in Europe, and soon engulfed the world. Very much the patriot, Raymond heard the call to action and in 1944 with four of his five brothers already enlisted, he left King Features and Flash Gordon, to join the Marines. He went through a tour of duty onboard a ship in the pacific and, ever the artist, worked on public relations material for the armed forces.

After Raymond returned from the war, King Features wouldn’t let him reclaim the strip, which in the meantime had been taken over by Raymond’s former assistant, Austin Briggs. Raymond instead ended up taking over the police procedural Rip Kirby, which true to his nature he also went on to build into a strip of some note.

Born in 1944, George Lucas undoubtedly grew up with the Flash Gordon comic strip, which has been continually drawn in various configurations and by a variety of artists since its inception. But while the comic strip was probably quite influential, Lucas arguably drew more on the serial for his initial inspiration. If for nothing else because it maintained the playful, adventurous nature that the strip had started out with, whereas the tone of the strip itself turned more and more serious. As the innocence of the world was lost in the great war, so too Flash’s adventures went from being high adventure to heavier more burdensome stories in which Flash sets out to unite the peoples of Mongo (much to the dismay of Dale, who worries mostly about when Flash will get around to marrying her).

In the days before television invaded the living room, a trip to the theatre to see the latest Hollywood epic entailed not only the film (and 30 minutes of commercials), but newsreels, animated shorts, and often film serials. Akin to TV shows, film serials have a long history in the early days of Hollywood, but ultimately broke their neck on the popularity of television when the economics stopped making sense. Usually about 20 minutes long, they were most often defined by their daring-do heroes, comic book villains and damsels in distress, most often set in the wild west, during the war, and often with some science-fiction elements sprinkled throughout. They moved fast, often to distract the audience from their lack of production value and gaping plot holes, and had little in the way of overarching story, so as to allow people who hadn’t caught one or more episodes to still enjoy the show. Some ran much longer, but commonly they would last for about 12 episodes, with each episode ending on a ‘How will they ever survive this!? Tune in next week!’-cliffhanger ending.

Television series would eventually take their place, but in the 1930s, despite the rising cost of sound production, Columbia, Universal and the newcomer, Republic Pictures, which was created only for serials, were still going strong. Much like today it didn’t take long for Hollywood to jump on a hot property like Flash Gordon, and by 1936 the first of three Flash Gordon film serials landed in theaters to uproarious success. This despite being the supposedly most expensive serial ever created up until that point.

Brimming with the kind of naive pluck that Mark Hamill would later bring to the role of Luke Skywalker, olympic swimmer (and USC alumni) Buster Crabbe became Flash Gordon. Already known for his role as Tarzan, with Flash Gordon the name Buster Crabbe became synonymous with heroics. So much so that when it came time for Buck Rogers to follow suit with its own serial, it was unthinkable that anyone else inhabit the role of Buck Rogers and Buster Crabbe was called upon again.

Today the serials seem quaint, not only for the stories and characters, but for the production quality, which is by all modern standards laughable. But for its time it was astonishing, easily living up to its beloved comic strip predecessor. Each episode brought a new danger to bear on Flash and his friends, monsters of every kind and tribes from all over Mongo (most often some sort of animal-based men; hawkmen, lionmen, apemen, sharkmen and so on). And though it was touted as being the most expensive serial production ever, every opportunity for saving money was jumped upon. Footage from Leni Riefenstahl’s silent 1929 film Die weiße Hölle vom Piz Palü would pad out the snow-climbing sections (and provide some much needed scale to an otherwise studio-bound production), and Flash would do battle on the steps of a medieval tower from The Bride of Frankenstein. In fact, the music that opened many of the serial’s episodes was a theme from The Bride of Frankenstein that had been co-opted (as was much of the other music used). The impressive idol footage in Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe was from the 1930 musical Just Imagine. Other medieval sets were used from Tower of London (1939), and footage was brought over from Perch the Devil (1927). In an unprecedented move the production shot on the sets of James Whale’s 1940 film Green Hellbefore he himself had put them to use!

The first Flash Gordon serial was followed in 1938 by Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars(you knew it would happen), the Buck Rogers serial also starring Crabbe in 1939, and almost indistinguishable from Flash Gordon, and finally Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe in 1940.

As the war drew to a close, the movie serial business had started slowing down some, and as the 50s saw the coming of television into the average American household, it all but signed the death warrant of what had once been one a staple of entertainment in the US. With TV came a new run of Flash Gordon, starting in 1954, though it never reached the success of its predecessor. At the same time however, the saturday matinee saw a revival as reruns on the smaller screen, and a new generation was introduced to the old serials, including of course Flash, still a favorite.

Lucas would sneak over to his friend John Plummer’s house to watch cartoons and serials until the Lucas’s finally budged and bought their own TV set in 1954. Their favorite show was Adventure Theatre, on at 6pm from the only TV station available in Modesto. This is where he he was first exposed to Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers and countless old war and adventure movies. Like any child at that age, he was transfixed, and his brain a sponge.

“I was appalled at how I could have been so enthralled with something so bad,“ [Lucas] recalls. ”And I said, `Holy smokes, if I got this excited about this stuff, it’s going to be easy for me to get kids excited about the same thing, only better.”’[kl303, 5]

Flash Gordon remains undeniably central to the creation mythos of Star Wars, and rightfully so. It was the go-to name for space adventure for decades, and one that endures to this day, albeit in today’s day and age it has retained more of a retro-kitch quality along the lines of Forbidden Planet. Nostalgic perhaps, but to most people simply quaint.

And for all of the attention Flash Gordon gets in relation to Star Wars, mentioned first in any list of influences, its real impact is less specific than it is spiritual. None of Lucas’s drafts ever really felt like a reprisal of the adventures of Flash Gordon; they lacked the square-jawed do-good nature of the Raymond strip or the Crabbe serial. Indeed they retained more tonality from the Kurosawa side of the family. It’s certainly possible to point to monsters like the Rancor and see echoes of the subterranean Gocko, or indeed a number of similar monsters. But the relationship between the two space operas is less one of specifics, and more one in which Lucas used the basic trappings of space opera to transpose the stories of Kurosawa.

Lucas’s first draft is a perfect example of this, being as it is a near scene-by-scene copy of Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress, only everything is set in a universe not dissimilar from that of Flash Gordon. Rocket ships, energy beam weapons and planet hopping et al. One of the tropes that Flash Gordon relied heavily on, which was reprised in the Star Wars films, was the use of natural environments. While Flash did very little actual planet hopping — with most of the stories taking place on the planet Mongo — each kingdom on Mongo was for the most part defined by a single type of terrain. Forest, snow, underwater. In Star Wars they would become (unlikely) planets, in which one type of terrain enveloped the entire planet.

If anything, what can be said of Flash Gordon’s actual influence would be its use of adventure tropes from across the board. It borrowed heavily from the kind of costumes used in medieval period films of the time, and much of its action, were it not taking place on the planet of Mongo, could have been from any number of swashbuckling adventure movies. Between that, the When Worlds Collide opening and it of course being a transposed copy of Buck Rogers, it actually pre-dated Star Wars’s borrowing by some forty years. Though how much this figured into Lucas’s thinking on the subject is impossible to say.

Alex Raymond, like Lucas, loved cars and speed. At forty-six he visited his colleague Stan Drake, who had recently taken possession of a brand new Corvette. Together they took it for a spin.

Failing to see a stop sign, Raymond lost control of the car in a rain-slick intersection in Connecticut on September 6th, 1956. Going well above the speed limit, the car slid into a steep fall before coming to a halt in a small grove of trees. Drake was thrown from the car and suffered severed injuries from which he eventually recovered.

Raymond died.

Drake who knew Raymond mostly as a colleague later learned that Raymond had been seeing a woman outside of his marriage. His wife however wouldn’t grant him a divorce. According to the hospital, this was the fourth time in that same month Raymond had been involved in car-related accidents[6].

Whether his death was truly a suicide remains something of a mystery. But whatever the case, his legacy remains.