Heavy are the shoulders that bear the burden of success.

In the years after the release of Star Wars, some people have placed the brunt of the blame for their perceived disintegration of mainstream film largely in the respective laps of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, for the sin of having invented the modern day blockbuster. Over the years as Spielberg diversified and garnered more critical acclaim (something he did not always enjoy), the blame shifted mostly onto Lucas, as exemplified here by Philip Kerr, film critic for The New Statesman, in a biting critique of Lucas and Star Wars on the eve of the premiere of Episode II:

Exactly 30 years ago, a young film director started to write a movie treatment that was a hybrid of Buck Rogers movies and the novels of Carlos Castaneda. By May 1973, all he had to show were 12 pages that appeared to indicate a greater interest in Castaneda’s experiments with drugs than in his New Age stories about a Yaqui Indian shaman who could manipulate the forces of time and space.

It continues

Before Star Wars, audiences were more sophisticated. They went to see films with special stories, not special effects. Lucas changed all that, perhaps for ever, helping to deliver a new kind of cinema: cinema as cheap amusement-park ride. In 1999, 22 years after its original cinema release, Star Wars was voted Britain’s favourite film, in what was claimed to be the biggest poll of its kind.

For people of my generation and older, it still seems almost inconceivable that such a film should be chosen in preference to Citizen Kane, Lawrence of Arabia, Les Enfants du Paradis or The Searchers. And I often think that Lucas has done more than any other man to bring into being the “feelies” - the sensation-led cinema described by Aldous Huxley in his futuristic novel Brave New World: “There’s a love scene on a bearskin rug; they say it’s marvelous. Every hair of the bear reproduced. The most amazing tactual effects.”

At the same time as turning cinema into Huxley’s “all-super-singing, synthetic-talking, coloured, stereoscopic feely”, George Lucas has reduced the critical response of the typical audience to a few gormless oohs and aahs.[1]kerr

It’s hard enough to take Kerr’s critique seriously when a cursory glance at his review record reveals him to be more interested in entertaining through vitriol than delivering opinions measured with insight. But it becomes almost impossible when he’s unable to make it past the first paragraph without wallowing in poor research. Chastising Lucas for only having 12 pages to show for by 1973, without going into how long he spent writing those pages, or what they contained? Should Casablanca be measured from its never-ending rewrites? Or Apocalypse Now for that matter? Neither film had their respective endings written when it came time to roll film.

Of course not, and one would be forgiven for thinking that Kerr’s attempted accusation was less a successful jab at an actual issue, and more an attempt at showing his deep knowledge of the making of Star Wars. No doubt lifted from the gossipy pages of the ‘revenge of the wives’ tell-all by Peter Biskind, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls.

Unfortunately for Kerr, he stumbles right out of the gate in his own factual inaccuracies. The 1973 treatment never mentions the force, there are no drug references at any stage in its development, and there’s quite frankly very little proof that Lucas even read Carlos Castaneda until after Star Wars was released. Nonetheless his piece is wonderfully representative for a group of critics (and film fans) who accost audiences for not going with ‘real’ films, the kind dealing with racism, murder, obsession, guilt, the lust for power, messiah complex, control, sexuality, materialism and so on and so forth (I’ve seen them all and love them dearly, but they are heavy fare). After all why spend friday evening with the family at a rip-roaring space adventure, when you can wallow in all the wonderful flaws of humanity and the underbelly of society?

While Star Wars may have been one of the first proper modern blockbusters, by the time it came out, James Bond was ready with its tenth installment (The Spy Who Loved Me in 1977), the majority of which can be said to have been of questionable quality, all of which certainly fall well into the territory of fluffy power fantasies and a lot of which made, and continue to make, a pretty buck at the box office[2]bond. No, the theatre going audiences of the late 70’s weren’t the critical film connoisseurs Kerr would like to make them out to be, the film makers were.

What’s also remarkable, and what Kerr completely fails to address, is that while Star Wars (and Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind) helped ring in the age of the blockbuster, they were still made in the more personal spirit of the New Hollywood directors. They were lighthearted and fun, but they never surrendered to indulgence.

Though American Graffiti is arguably Lucas’s most personal endeavor, when you look back at Lucas’s life and career up to the making of Star Wars, what is so remarkable is that everything points to that moment. Yes, Star Wars is a rollercoaster ride of a movie, in some ways the first in what has now become Hollywood’s main mealticket. But it’s also at its heart a deeply personal movie. Lucas drew not only on the movies and books he liked, but on his childhood and adolescence.

Contrary to most modern blockbusters, Star Wars has a soul, and a spiritual center. And that’s why it endures.

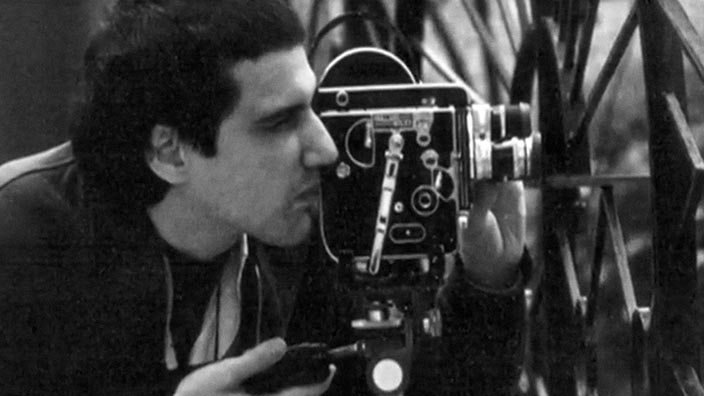

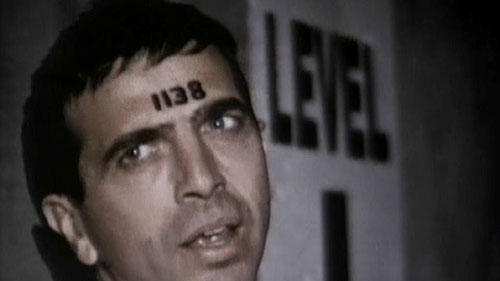

But beyond this naval-gazing and overly simplistic attitude towards the film industry, what’s so marvelously ironic about this particular example, and what Kerr fails to mention at all, is that Star Wars is in the unique position of, in a sense, having been made twice. One for the masses — you know it as Star Wars — and another, six years prior – almost sinking Lucas’s career before it ever started, because the so-called ‘more sophisticated’ audience, never showed up to see it. You know it as THX 1138.

The audience voted with their money before Star Wars was even conceived, its popularity simply gave surly old critics and film snobs an easy target for their frustrations with an industry that is ultimately a business, slowly improving itself as such.