The Mœbius Probe

One of art legend Mœbius’s smallest comic book doodles grew to a starring role in Star Wars II.

Following the adventures of spatio-temporal agents Valérian and Laureline as they hurdle through time and space, righting wrongs and getting out of tight jams, Mézières and Christin's trend-setting comic series was lightyears ahead of its time.

Future writer Pierre Christin and artist Jean-Claude Mézières first met each other when their respective families sought refuge in the same bomb shelter in Paris during World War II.

They remained friends and both spent time in the US when they were younger. Mézières was deeply in love with the American west and worked as a cowboy for some time, and the two even met up in Utah, where Christin had his tenure as a professor of French Literature at The University of Salt Lake City.

Together they dreamt of creating a comic together, a timely dream as in particular French and Belgian comic books unprecedentedly popular. Much to Mézières’s initial disappointment they soon ditched their original idea to do a wild west-style story, because that genre was so saturated already. Christin however had picked up a love of science fiction during his stay in the US, and suggested that they try their hand at that, since it was a genre which was underutilized at the time.

And so was born Valérian and Laureline (Valérian et Laureline in their native French), first published in the the long-running French comics magazine Pilote in 1967, a series that lasted no less than 43 years, before finally ending with the publication of the twentieth album in 2010.

Valérian and Laureline is the continuing story of the two namesakes — the black-haired, straight-guy Valérian and the enticing redhead Laureline, a peasant girl from the middle ages French countryside — both agents for the space-time police of Galaxity, the capital of the far-future Terran galactic empire.

In their saucer-like spacecraft, they travel across time and space on a variety of missions and adventures, encountering diverse civilizations, assorted exotic creatures, locales and danger at every turn. Sailing around a flooded New York in one volume (a nuked North Pole, in case you were wondering) and taking in an inter-galactic cruise peopled with races of all shapes and sizes in the next.

The series walks in the footsteps of Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury and their contemporaries, making wide use of similarly veiled environmental, political and social allegories, and was hugely successful, at least in Europe, and remains widely regarded as a classic piece of science fiction. It's been translated into more than sixteen languages and has sold more than three million copies worldwide.

In terms of raw visual influence on fantasy and science fiction, it’s hard to not talk extensively about the contributions of Mézières and his work on in particular Valérian and Laureline, as well as his friend Jean Giraud AKA Moebius, and his work. Their combined influence is frankly impossible to overstate, and in terms of film their reach is equally impressive, to this day.

However where Moebius worked directly on several films, including Alien, TRON, Willow and The Abyss, Mézières, despite his work having such a wide and deep influence, worked only on The Fifth Element, alongside Jean Giraud as it were.

That however didn’t stop many other films, including Star Wars, from drawing on the visual splendors of these seminal French artists.

Kim Thompson in the introduction to the 2004 edition of the Valérian series The New Future Trilogy:

In 1977 Mézières sat down in a movie theater to enjoy a new movie called Star Wars and was astonished to see how many of the designs and concepts-and, indeed, the whole motif of a lived-in, funky future-seemed awfully familiar. Polite inquiries to the Lucas camp went unanswered, but over the years word leaked back that the Star Wars designers (some of them French) had indeed maintained a nice collection of Valerian albums.

It’s possible Kim Thompson is mixing several things together, but as a matter of housekeeping, the French designers mentioned might refer to someone working on the prequels. Doug Chiang, the art director on Episode I had Valérian and Laureline as part of his research library for instance. But to the best of my knowledge, there were no French artists working on the original trilogy.

Regardless, around the time of the release of Return of the Jedi in 1983, Mézières was interviewed for the 113th issue of Pilote magazine (Oct. 1983) in relation to a new volume of Valérian and Laureline, and revealed that “Obviously I’m angry, jealous… and furious!”. He argued that yes, Lucas had been inspired by all the same books that he and Christin had been drawing on over the past 15 years, but that he was quite certain that Lucas had specifically glanced at Valérian and Laureline for Star Wars.

Mézières even reached out to Lucasfilm[1], reportedly on more than one occasion, but never received a response, and continued to point fingers no only at Star Wars, but also at Conan The Barbarian and Independence Day, finding several similarities between either of them and his work on the comic-book series.

But Star Wars in particular irked him. So much so, that he made a drawing for that same issue of Pilote, in which a bikini-clad Leia, and a dark-suited Luke share a table in a bar crowded with all manner of aliens, with Valérian and Laureline. “Fancy meeting you here,” says Leia, to which Lauraline responds “Oh, we’ve been hanging around here for a long time!”

Perhaps Mézières felt that in particular Hollywood had overlooked his artistic contributions to the fantastic genres, or perhaps he simply felt like setting the record straight. The Pilote interview and drawing combined with several pages of the official website being dedicated to this exact topic certainly makes it seem like something that has weighed on him over the years.

The website calls out very specific examples, some of which we’ll address here, but the most interesting one is a bit more holistic, namely that of the ‘used universe’. In the world of film, Star Wars famously broke with the often very sterile look of science fiction films by having dirty, banged up spaceships, dusty desert settings and ruffled clothes. This was something Mézières had worked with from the beginning of the Valérian series, creating very believable, messy scenes crowded with a colorful array of aliens and creatures, often clad in rags, nomadic clothes and the like.

By the mid–70s when Lucas was working on Star Wars, that aesthetic however wasn’t as unique as it was when Valérian had first premiered, so while it’s plausible that Lucas drew on Mézières and Christin’s diverse, used galaxy, it was arguably also something that by then had infiltrated deep into the zeitgeist through outlets like Heavy Metal magazine. Mézières may have gotten there first; but he wasn’t alone for long.

Valérian was a hit in Europe, but like so many European comic books it (unfairly) never did manage to catch the American market, to whom the characters and stories lay perhaps too far from the Superman descendants they had grown accustomed to. All of that said, Lucas was a card-carrying comics connoisseur, whom together with his Super Snipe Comic Art Emporium partner Edward Summer, did a lot of business in France in the years he was working on Star Wars. I know this because Edward Summer himself told me as much, although I never did get to ask him about Valérian specifically.

I've argued earlier that the filmic ancestry of Star Wars’s used world probably hailed from Carlo Simi’s work on Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns, and I stand by that assessment as I believe that production design on films, in particular before the modern superhero wave, remains indebted to films more than to books or even comics, visual though they may be (see the clear similarities between the cantina and Production Designer Carlo Simi's sets for just one example).

Keeping all of this in mind, I feel that without any quotes on the matter from people close to the production of Star Wars, the origin of the lived-in feel for science fiction can go to a number of contenders, even if Mézières pioneered it.

That said it is hard to look at Mézières' panels and not feel that while the cantina for instance clearly borrows from Casablanca and Leone's works among many others, its peculiar denizens might very well have sprung from the pages of Valerian.

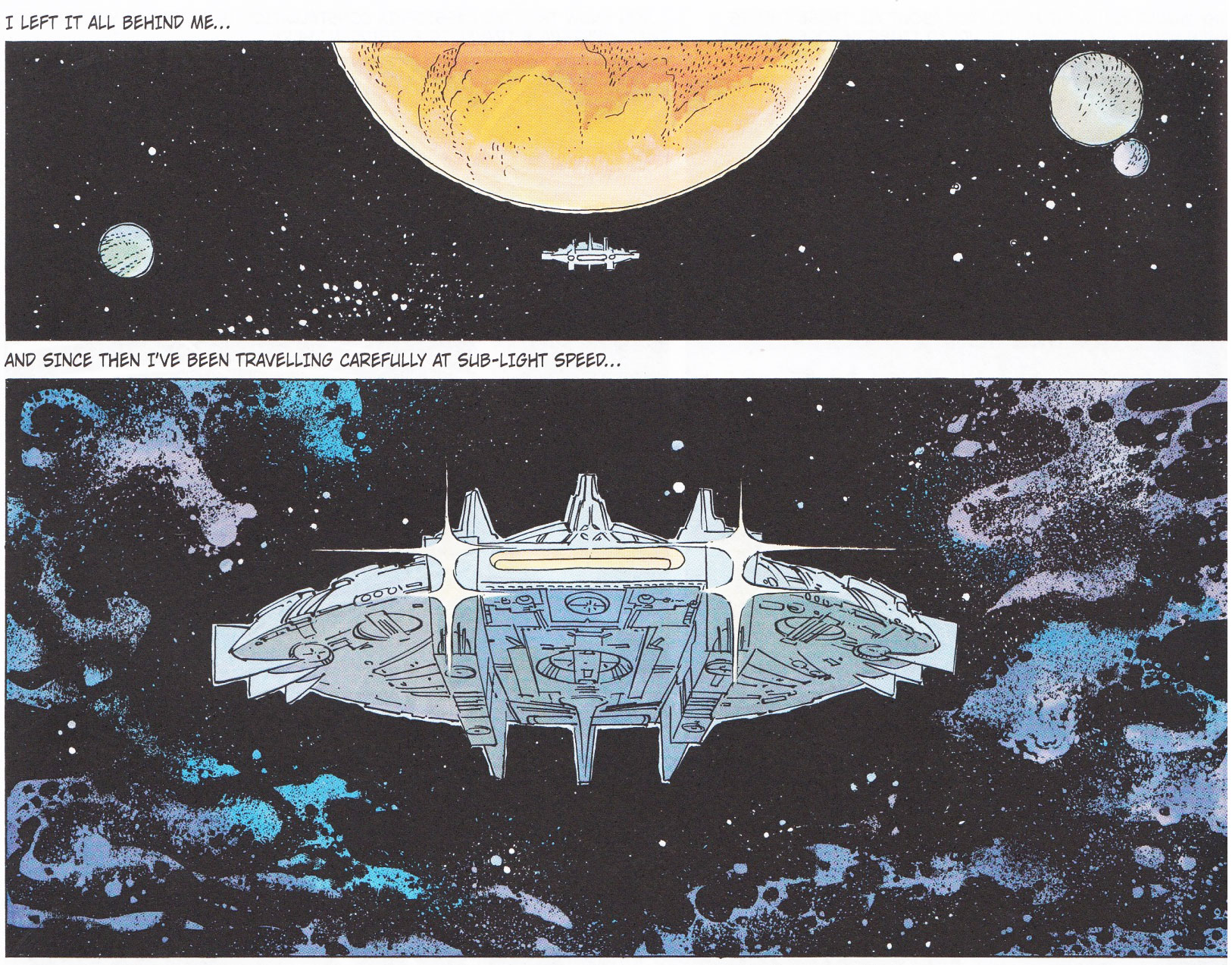

One of the more specific points of contention, listed on the official website, as well as in Cinebook ltd’s 2011 english language version of L’empire des Mille Planetes (The Empire of a Thousand Planets), first published in 1971, is the claimed influence from the saucer-like ship Valérian and Laureline use to travel through space and time, the XB982.

Its design changes a bit here and there across the series, but it is generally portrayed as an oval, saucer-like craft, with three long fins, one in the middle and one on either side, running from the front down along the length of the ship, both over and under, protruding to the rear like rudders. The front is marked by an elongated pill-shaped yellow slit, the cockpit window, and on the rear its thrusters are most often a series of circular red dots on the end. In some instances it has three cross-bar-like protrusions on either side, and the landing gear, three legs to either side, extending like those of a spider.

The obvious comparison is with the Millenium Falcon, also a saucer-based design, and indeed many of the shots of the Falcon are easily compared to the XB982, especially because the XB's viewport so easily stands in for the Falcon’s rear-thrusters.

Click to zoom.

But at the same time, the Falcon’s cockpit and mandibles, protruding from the saucer-shape, as opposed to the large fins on the XB982, make the comparison seem a little far-fetched. Yes, the two share a saucer-shape, but then so does most of the spaceships that came out the 50s. In fact, if we go back to the poster for 1957’s Invasion of the Saucer Men, we see several saucer-like ships, the ones supposedly carrying the men of the title, with fins running along the underside and a silhouette similar to the XB982. Coincidence, or inspiration? Does it matter?

Whether the Falcon draws on Mézières’s design is anyone’s guess (mine after having done extensive research on the subject is that it likely doesn't). The Falcon went through numerous designs, starting out as what would become the Blockade Runner before it was changed to the new design. The saucer design shares the basic saucer shape, yes, but even there the two are not quite the same.

Speaking in favor of the XB982-based design notion is that fact that Joe Johnston seemingly drew from an 8-page short story written and drawn by Mézières published in Metal Hurlant No. 7 in French in 1976 under the title Baroudeurs de l'espace (Space Legionares)[5]. I don't know when it was first published in English, but given that it was released in Spanish in 1977, it would make sense that it would make its way to English around the same time, which as it happens was exactly when The Empire Strikes Back was ramping up pre-production in the wake of the surprising success of Star Wars.

On the left is a panel from Mézières also with soldiers carrying satchels across their shoulders, and on the right Joe Johnston's drawing of snow troopers carrying satchels across their shoulders[4], having just dis-embarked an AT-AT (with it's Syd Mead inspired feet) on Hoth. According to J. W. Rinzler's The Making of The Empire Strikes Back, Johnston's sketch, numbered 0036, was finished in late 1977 “after Lucas had requested a larger walker”.

It’s possible that the idea of having the Millennium Falcon at the center of each of the original films, employing it for everything from simple transportation to outrunning pursuers or crashing into uncharted territory, sprung from the Valérian’s use of the XB982, which followed the two agents through thick and thin. But personally I pin that idea on Howard Hawks' Air Force; not that it has to be mutually exclusive, but I think it is.

Conversely, maybe Mézières and Christin were inspired by Star Wars, when the XB982 crashes into a burnt out forest of an unknown planet in Les Armes Vivantes (The Living Weapons, 1990), after which Laureline dons a breathing mask and exits the XB982 to investigate the surrounding area, similar to how Han, Leia and Chewie exist the Falcon in the belly of the space slug in The Empire Strikes Back.

Other similarities often pointed out includes the resemblance in appearance of Grand Moff Tarkin, played by veteran british actor Peter Cushing to the Ambassador from Ambassador of the Shadows (1975), which while striking, is hard to take seriously as a ‘rip-off’. After all the production needed to employ a large number of british actors for financial reasons, and Cushing was one of England’s most well-recognized faces and renowned actors.

Another similarity is Leia’s ‘slave’ outfit from her stint as Jabba’s concubine in Return of the Jedi, which is compared to a similar outfit worn by Lauraline at one point in the series. A striking similarity to be sure, but a shallow one given the history of the often sexually exploitative pulp genre.

“Egyptian Queen” by Frank Frazetta (1969)

The design may very well have been directly influenced by Lauraline’s bikini, but Mézières in turn was far from the first to have spiced a fantasy tale up with a scantily clad woman; a tradition harking back at least to Edwin Lester Arnold’s Gullivar Jones and his mis-adventures on Mars, and of course its descendants in John Carter and Conan, if not further.

Perhaps most iconic was Frazetta’s Egyptian Queen from 1969, which was specifically called out by Aggie Guerard Rodgers, costume designer on Return of the Jedi, as an influence.

The most damning similarity occurs in L’Empire des Milles Planètes (The Empire of a Thousand Planets, 1971), when Valérian is encased in a transparent, orange-tinted brick of plastic. Although he retains his consciousness while encased in this block, the scene is otherwise in many regards strikingly similar to Han Solo’s encasing in carbonite in The Empire Strikes Back, complete with his hands in a ‘reach for the sky’ pose.

It becomes even more suspicious when a helmet-clad, cape-wearing man continues to interrogate him, before removing his helmet, revealing a burnt, scarred face underneath. There are many other similarities that can be brought to bear; the way Mézières draws a fleet of ships for instance is very reminiscent of how they show up in Episode V and VI, and that’s not even mentioning the prequels.

As these comparisons bounce around magazines, books and now the internet, it draws the picture of snubbed artists who saw their ideas made into billions of dollars without any recourse for them, and an embittered decades long hatred against the American film maker who stole them.

But that's not quite the story Martin Scholz of Die Welt got when he interviewed Christin in January, 2016 hot on the heels of the release of The Force Awakens (I'm quoting the Europe Comics translation).

Die Welt: It was in 1967 that the first story of your science fiction comic strip featuring the space cops Valerian and Laureline came out. Ten years later, the first episode of Star Wars was released in cinemas. Strikingly, both this film and its sequels borrowed heavily from your characters, creatures and even from the design of your spaceships.

Pierre Christin: Yes, that’s exactly what my colleague Jean-Claude Mézières and I told ourselves when we walked out of the cinema after watching Star Wars for the first time. But my first reaction was not anger.

Die Welt: What was it then?

Pierre Christin: I was thrilled. I watched the film in one of the local cinemas of the Parisian quarter of Montparnasse, where I live. Star Wars was the science fiction film I had been waiting to see. Besides a few exceptions, the other films of the genre were mediocre at best, particularly when it came to the visual effects. I instantly felt connected with Star Wars because of the number of intersections and parallels with our comic strips. George Lucas had created complex worlds, just as we had. Like us, he had staged the functioning of societies from within, although Star Wars focussed perhaps a bit more on the struggle between good and evil. In this respect, Valerian was more European, more intellectual. For my part, this comes from my fascination for science fiction novels by authors like Isaac Asimov and Ray Bradbury. I am sure George Lucas has read Asimov as well. That’s how it goes in sci-fi: It’s all about copying from one another. Or, in other terms: You borrow something from someone else and develop it further. In any case, Star Wars was a huge, positive surprise to me. I loved the characters.

Die Welt: Now that sounds rather conciliatory. But you and your colleague Mézières once drew an illustration for the French comic magazine Pilote, showing your heroes Valerian and Laureline sitting at a space bar table with Luke and Leia Skywalker. Your heroine teases: “We’ve been regulars here for a while now.” Is that your nonchalant way of asking the authorship question?

Pierre Christin: In the 80s, particularly in France, people were convinced that George Lucas had stolen from Valerian. This particular drawing was our way of addressing the question in a satirical manner. In general, all you hear from the US in reply to such allegations is that French comics are barely known and not successful at all on that side of the Atlantic – which, on the whole, is true. Nevertheless, the few people in the US who do know French comics fairly well are Hollywood’s art directors and storyboard artists. They might not be able to read the magazines, but they still flick through them now and then in search of ideas. That’s what French film-makers who’ve been to Hollywood have told me: They happened to have seen piles of French comics in the creative departments of various film studios.

Die Welt: Steven Spielberg is one of the few US film-makers to have acknowledged this influence. He has given credit to famous cartoonist Hergé, creator of “Tintin”, describing him as a screenplay writer with a crayon. Shortly before Hergé died in 1983, the two had a telephone conversation. In 2011 Spielberg released his computer-animated film The Adventures of Tintin. Has Lucas ever tried to get in touch with you?

Pierre Christin: No. And that was not very comme il faut indeed. Lucas could have contacted us, even just to say “merci” – as a polite gesture, some kind of acknowledgement. But that is how the Americans in Hollywood are. Most of them aren’t bothered about what other artists did in other parts of the world. They don’t hesitate to help themselves. This applies to many film-makers in the US.

Die Welt: Let’s talk about some of the more apparent parallels between your comics and the Star Wars episodes. In The Empire Strikes Back of 1980, Han Solo is frozen in a carbonite block – Valerian had already suffered a similar fate in Empire of a Thousand Planets in 1971. Even their haircuts look alike.

Pierre Christin: Well, they both happen to be heroes of the 70s. Han Solo’s and Valerian’s haircuts are quite the same. On top of that, our characters and the ones in Star Wars share a particular sense of humour. When something goes wrong, they can live with appearing ridiculous in that particular moment. They are not the typical heroes who come up with a solution to every problem. The couple configuration – Valerian and Laureline vs. Han Solo and Leia in Star Wars – reinforces the humoristic elements. Men and women teasing each other can always come across as very funny. That was completely new to the science fiction genre – be it comics or films.

Die Welt: Laureline had already revealed to comic readers in 1972 a metal bikini quite similar to the legendary costume of Princess Leia in the 1983 episode Return of the Jedi. And Han Solo’s Millennium Falcon looks confusingly similar to Valerian’s spaceship. Didn’t that bother you at all?

Pierre Christin: You know, my colleague Jean-Claude and I are quite positive fellows. We took that more as a compliment. But following the tremendous success of “Star Wars”, we came up with a sort of counter-reaction. For a decade we had Valerian accomplish interplanetary adventures of all kinds. We had him take on aliens, exotic cultures, tyrants and evil forces. After Star Wars had absorbed all these motifs into its neighbouring universe, we knew we had to change our story.

Die Welt: So did your comic empire strike back?

Pierre Christin: Somehow, yes. That’s when we decided to develop the cycle Châtelet Station, Destination Cassiopeia that sees our time travellers sent back to Earth and the present time. So we can say that Star Wars has also had an influence back on us. Even if we had wished for some kind of recognition, I’d still admire the films. A villain like Darth Vader is simply a cinematic flash of genius, destined to be a great film icon forever. The reason we fear him so much is because he partly reflects ourselves.

• • •

There are strong similarities, yet there are also plenty of differences, certainly in characters, but also in tone, in design choices and in storytelling.

And more importantly, while Valérian and Laureline was groundbreaking in its own right, it's worth noting as Christin also says in the above interview, and he and Mézières themselves weren’t above reproach when it came to inspiration, drawing in elements from Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Jack Vance, John Brunner, Jean-Claude Forest, Georges Simeon, Ed McBain and Paul Anderson[2].

The very concept of spatio-temporal agents itself comes from Isaac Asimov’s The End of Eternity, with the idea of a galactic empire probably stems from Asimov’s Foundation series, and in an article posted on the official Mézières site, the authors even note that the series “is a self-conscious strip teeming with references to science fiction and mainstream literature, movies, and canonical European and U.S. Comics”[3] Not to mention the even then time-honored traditions of the sword-and-planet genre.

Without Flash Gordon and John Carter, there would have been no Valérian or Laureline.

Black Drawings by Jean-Philippe Guerand. Published in The New Cinema, Nov. 1999.

Valérian and Laureline Wikipedia page, retrieved Aug. 26, 2013.

Jean-Claude MEZIERES. Adapted from the original text in European Readings of American Popular Culture. Edited by John Dean and Jean-Paul Gabillet. Contributions to the Study of Popular Culture, Number 50. Greenwood Press, Westport,Connecticut. 1996

'Imperial troopers and walker feet' by Joe Johnston was first printed in black and white in The Empire Strikes Back Sketchbook from Ballantine Books, the first edition of which was released in 1980. It may also appear elsewhere, but it is also printed in J. W. Rinzler's The Making of The Empire Strikes Back, page 34, Aurum Press, 2010.

The complete 8 page story of Space Legionnaires is available online, for those so interested, although seemingly only in Spanish.

Riders astride giant lizards might not have been an entirely novel concept by the mid 70s, but Ron Cobb's take on it had an air of the fantastic, while being grounded in reality. Cobb would go on to work on creatures for Star Wars , and this early design probably inspired the Dewback.