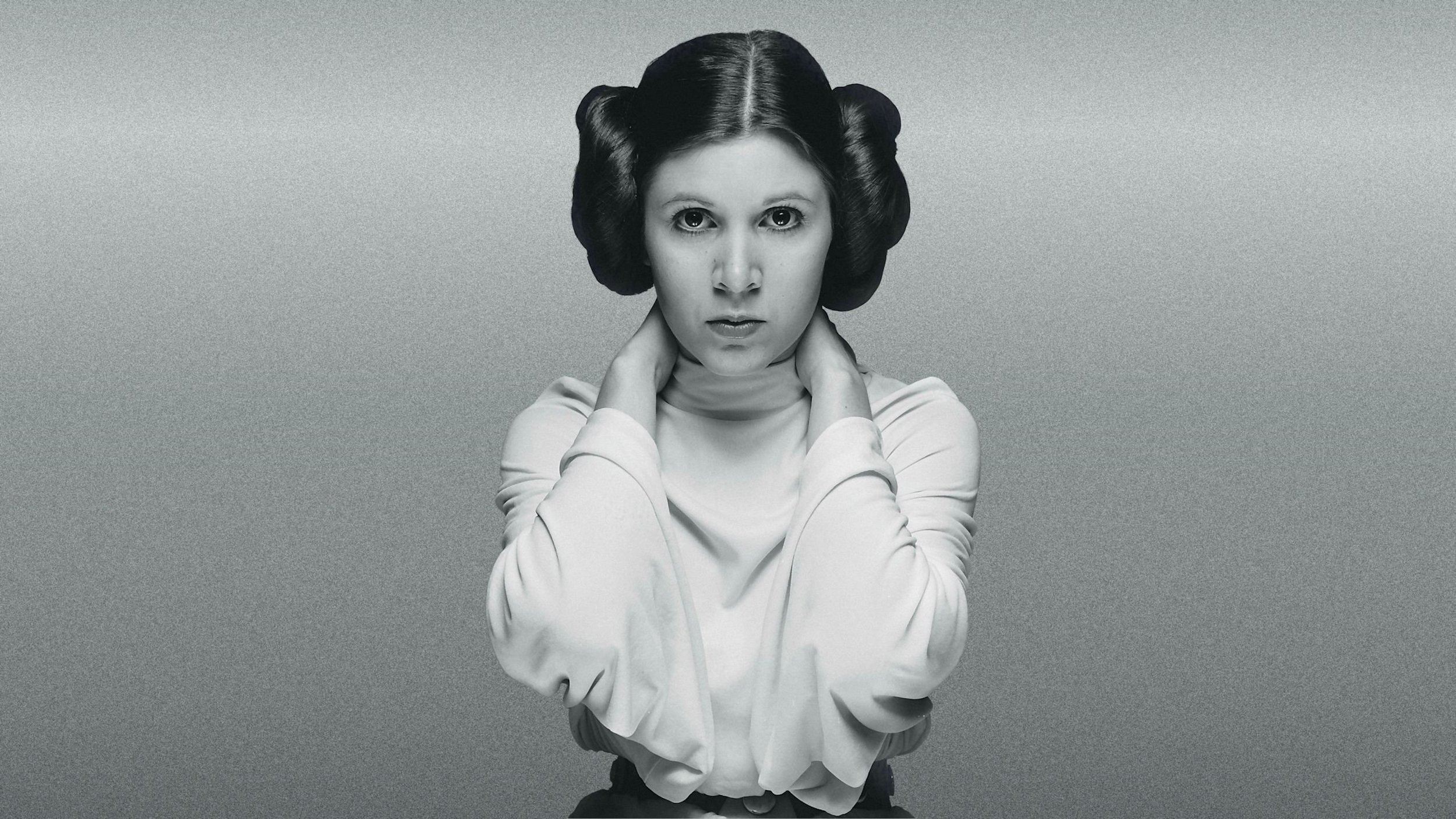

This book is a tribute to the wonderful comic art of Al Williamson. It depicts only a small part of Al's vast contribution to the genre—his work on the Star Wars comic strip during the early 1980s. Combining Al's talents and the Star Wars saga was a natural, but few people know that it almost didn't happen.

I grew up in the era of comics. Even after television permanently entered American homes, I loved the fantasies of Alex Raymond. They showed boundless imagination, heroism, and a remarkable cinematic dimension.

I didn't know it back then, but Al Williamson shared my love for the genre, particularly the Flash Gordon series. It was no wonder that I became a real fan of Al's work for EC Comics.

When Marvel was looking for an artist to illustrate the first Star Wars comic book, I immediately thought of Al. Unfortunately, Al was tied up on a newspaper strip and unavailable.

After Star Wars was released, we decided to do a syndicated comic strip as well as the continuing series of Marvel comics. Again we approached Al. For a variety of reasons, the time just wasn't right and we had to go forward with another artist, who soon became very ill and could not continue the strip.

Now Al approached me. He wanted to revive the strip, in collaboration with Archie Goodwin, a very talented comic writer. We were about to begin shooting The Empire Strikes Back, so I was more than a little preoccupied. With some hesitation, I agreed to go forward.

I'm glad we did. The result is a body of work that makes a great contribution not only to the art of Star Wars but to comic art in general. I'm especially happy that we can present Al's work in this collection, reproduced with the quality and detail that shows it best. I hope that it will inspire a new generation of artists and filmmakers.

—

Finally here’s the introduction Lucas wrote for the 2007 book Alex Raymond – His Life and Art.

Alex Raymond – Introduction by George Lucas

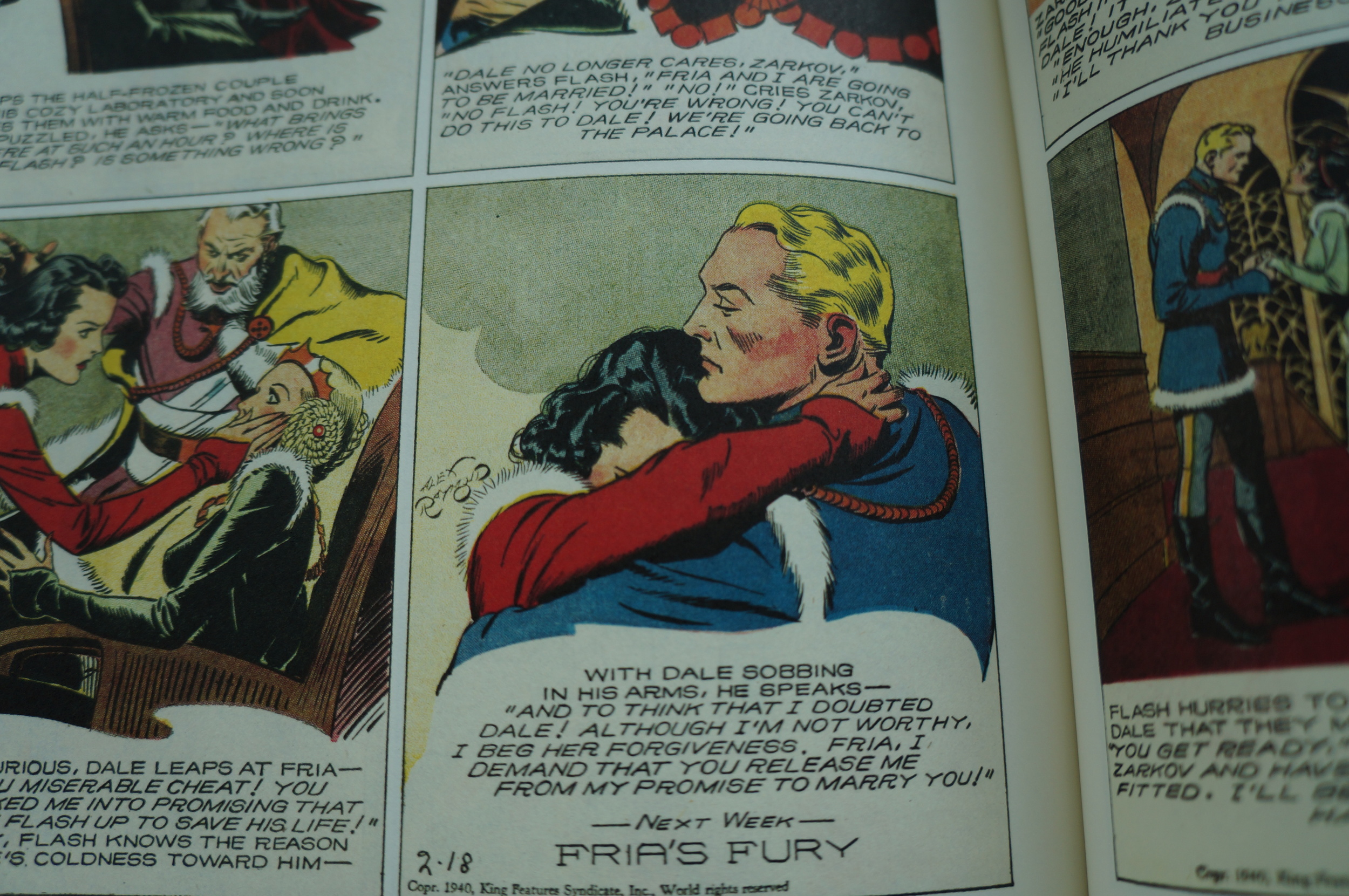

Growing up in California, I was enchanted by two things … race cars and Flash Gordon. The first love I put to use in American Graffiti; the second eventually turned into Star Wars.

As a boy I was enthralled by the escapades of Flash Gordon, both in the Saturday Matinee Serials, starring Buster Crabbe and the Sunday Comic pages. The unending adventures always left me wanting more. It provided the perfect “escapism” for my young mind.

Not many remember this, but before Star Wars was born, I first approached King Features Syndicate, the license holders of Flash Gordon, about securing the rights to make a feature film. The idea seemed perfectly fitted to the screen. Due to monetary differences this never happened.

I was still determined to make an epic fantasy film—something the kids would enjoy. I chose to make my own variation on the space fantasy theme. Just as Raymond had drawn inspiration from Jules Verne and others, I drew inspiration from Raymond. Combining it with bits and pieces from all my favorite mythologies. I put together the initial ideas for Star Wars. Had it not been for Alex Raymond and Flash Gordon, there might not have been a Star Wars.

In looking at Raymond’s illustration work, what is most evident was the versatility the man possessed. He could draw a fantasy creature or a Marine writing home and make you believe it. His illustrations contain the same grace and power, the same sense of dignity as found in the comic strip work. The quiet, thoughtful serenity of his Marine paintings give us a glimpse into the character of the man behind the pictures. One also notes the care that went into the work itself.

Alex Raymond’s boundless imagination has inspired me and countless others to pursue their own fantasies. His presence is still felt and remembered so many years after his death, and he has directly or indirectly touched u all. I for one, am very thankful for his inspiration.

George Lucas,

San Rafael, California