The Millennium Falcon

It's the ship that made the Kessel Run in less than twelve parsecs.

The in-depth look at the creation of everyone's favorite walking carpet. From the earliest idea, and the word 'wookie' in THX 1138, up through his visual development, through an unexpected twist.

The creation of Star Wars is a comprehensive mythology onto itself, populated by rarely documented anecdotes, like how The Millenium Falcon was inspired by a hamburger, with the cockpit being an olive off to the side” [1]databank:falcon (took me years, but I finally disproved that one) or “My original inspiration for Chewbacca was my dog Indiana.” [2]charactersofstarwars, compelling enough to be repeated until they’re so prevalent that they must be true, and are accepted even by hardcore fans and Lucasfilm itself. Unfortunately sometimes they’re embellished truths or half-truths, sometimes entirely false and in pretty much all cases oversimplifying a truly interesting, and luckily exceptionally well documented creative process.

And that’s what this is about; the creative process. Cultural touchstones like Star Wars might seem to have sprung fully formed from the minds of their lauded creators, but as in all creative endeavors, movie making, web design or this very post, nothing could be further from the truth. Creation is a process, and strangely, by looking at how everyone’s favorite plushy first-mate sprang into existence, we can learn a lot about any collaborative creative endeavor.

Unfortunately, perhaps because of the verisimilitude of the disciplines needed to make a film like Star Wars come together, the making-of narrative is surprisingly fragmented and often incomplete. A quick look at the bibliography needed to put together this post should give a good idea of just how fragmented. And once you’re down the rabbit hole, you quickly learn that nothing found there can be taken at face value. Quotes, drawings, photos and diagrams lack sources, are undated, some old, some new, some so distorted as to be pure fiction and most of it entirely out of context.

But while the official sources are often great, compiling from many different sources to dispel myths about Boba Fett’s ship, Slave 1 or tell in staggering detail the creation of the film from beginning till end as in the case of books like The Making of Star Wars, there are still plenty of dim, and in some cases even seemingly purposefully blacked out areas in the development of Star Wars.

The story of how Chewbacca came to be is one of these. A fascinating look at what happens in the space between idea, page and screen.

We start our story with George Lucas’ silver screen directorial debut, THX 1138, a simultaneously proto- and an anti-Star Wars. It’s probably early 1970 and Walter Murch and George Lucas are taking turns day and night editing picture and sound on the film in the upper floor of Lucas’ Mill Valley home, to get it ready for what will be a disastrous screening for studio executives, all but sinking Coppola’s just formed American Zoetrope studio [p. 42, 3]cinemaofgeorgelucas.

Walter Murch: “[We] got hold of some improv actors, and among these was Terry McGovern who was also a radio DJ. We would sit them around the table and give them each an identity, and in the middle of this dialogue you can hear Terry McGovern say ”I think I just ran over something back there, I think I ran over a wookie“. This is the first emergence of the word Wookiee as we know it today. And the small wookiees in THX who lived in the shell of this environment became the large wookiee that we all know in Star Wars.” [4]artifact

A shell dweller.

Source: THX 1138 (1971), Laserdisc release.

There is no direct connection made on film between the off-hand wookie remark and, as they are more commonly known, shell dwellers. But following the assumption that they are the same, it’s still hazy where the concept came from. Laden with overt social and political commentary, the hairy dwarf-like creatures may have sprung into life as a reflection of fringe existences, sacrifices of the consumer society and so on. Maybe at the hand of Lucas, maybe Murch, the two having written it together. But aside from the nickname and some unkempt hair, there is little else binding them to the latter-day wookiees of Star Wars, though both seem to have sprung from monkeys in some way.

“And later on after the recording I asked Terry ‘What’s the Wookie?’ and he said ‘Oh that’s a friend of mine who lives in Texas, Ralph Wookie, and I just threw his name in there as I always want to stick it to him and thought he’d get a kick out of hearing his name in a film’. Little did Terry know what kind of thing he was creating, this off-hand phrase has since become a character that literally billions of people probably know about.” [4]artifact

A few years later, in early 1973, as American Graffiti — a considerably less obtuse film, and with the possible exception of Wolfman Jack, devoid of wookiees — is taken away from Lucas by the studio and hangs in limbo, the first confused step towards Star Wars — then named The Journal of the Whills — introduces the name Chewie. Or more accurately, Chuiee, the writer of said journal.

Chewbacca, the character, also started his life in the rough draft (May 1974) as a kind of barbarian alien prince on the jungle planet of Yavin:

[…] five Wookees, (huge grey and furry beasts) […] The eight foot Chewbacca, who resembles a huge, grey bushbaby with fierce baboon-like fang […] [][5]roughdraft

Wookees communicate in grunts and whines and are in some respects close in character to what ended up on the screen, but far from in role. Also, there’s some stuff about a bonfire party and yodeling (seriously).

Furthermore in the rough draft, Chuiee permutes into the Chewie we know, though here it’s attached to ‘a young hotshot [fighter pilot] of about sixteen years’, who for the following draft has his named changed to Boma Two instead, presumably because Chewie and Chewbacca were too alike.

Boma Two dies by the way, spoiler alert.

Ralph McQuarrie: “[George Lucas] visited with his friends at my place and talked about a big space-fantasy film he wanted to do. It didn’t have a title yet.” […] “Well, a couple years went by and George did American Graffiti. I never thought I’d see him again, and then one day he called to see if I’d be interested in doing something for Star Wars.” [6]starwarscom

Ralph McQuarrie was hired by Lucasfilm Ltd. in November 1974, though he didn’t start working until January the following year, just as Lucas was putting the finishing touches on the second draft.

Ralph McQuarrie: “I’d sit with a pencil and dream about whatever I could imagine, sort of grotesque imagery. George would come by every week and a half or two weeks, look at what I’d done, and talk to me about what he’d like to see. I was reading the script to start with, but the script sort of got waylaid — the story was changing in his own mind — so George would just come and talk to me about what he wanted to see.” [6]starwarscom

Ralph McQuarrie: “George thought of [Chewbacca] as looking like a lemur with fur over his whole body and a big huge apelike figure. I took another track, added an ammunition bandolier and put a rifle in his hands. I had shorts on him and a flak jacket and all kinds of gear, but that was edited out.” [p. 44, 7]annotatedscreenplays

It’s remotely possible that McQuarrie got in early and influenced the script, though unlikely, and his statement actually clashes with the second draft, which quite explicitly states what Chewbacca is wearing:

Han turns to his companion, CHEWBACCA, an eight foot tall, savage-looking creature resembling a huge gray bush-baby monkey with fierce “baboon”-like fangs. His large yellow eyes dominate a fur-covered face and soften his otherwise awesome appearance. Over his matted, furry body, he wears two chrome bandoliers, a flak jacket painted in a bizarre camouflage pattern, brown cloth shorts, and little else. He is a two-hundred-year-old “WOOKIEE”, and a sight to behold. Han speaks to the Wookiee in his own language, which is little more than a series of grunts. The young pirate points to Luke several times during his conversation and the creature suddenly lets out a horrifying laugh. Han chuckles to himself and turns back to Luke. [Scene 43, 8]seconddraft

Three sketches of Chewbacca by Ralph McQuarrie"

Sources - Left: A Gallery of Imagination at Celebration V (2010) / Center: StarWars.com interview (2004) / Right: The Art of Star Wars, page 66.

Bushbaby Chewbaccas face

Source: Left & center: The Characters of Star Wars / Right: Unknown

None of McQuarries drawings in this article are dated, but we can infer some rough dates from looking instead at his production paintings. Here the second draft rescue of Deak, in which Chewbacca is still a lemur, dated March 28th, 1975 [p. 43, 9]rinzler2007.

The rescue of Deak from Alderaan by Ralph McQuarrie

Source: The Art of Ralph McQuarrie, page 177.

And again in this poster dated April 1st, 1975 [p. 41, 9]rinzler2007.

Promotional poster idea by McQuarrie

Source: The Making of Star Wars, page 41.

Chewbacca then goes on the back burner for a while. It’s even quite possible that he was considered ‘done’, awaiting production to ramp up. At least he doesn’t show up in any other pieces of artwork, until suddenly…

Ralph McQuarrie: “George also gave me a drawing he liked from a 1930s illustrator of science fiction that showed a big, apelike, furry beast with a row of female breasts down its chest. So I took the breasts off and added a bandolier and ammunition and weapons, and changed its face so it looked somewhat more like the final character, and I left it at that.” [6]starwarscom

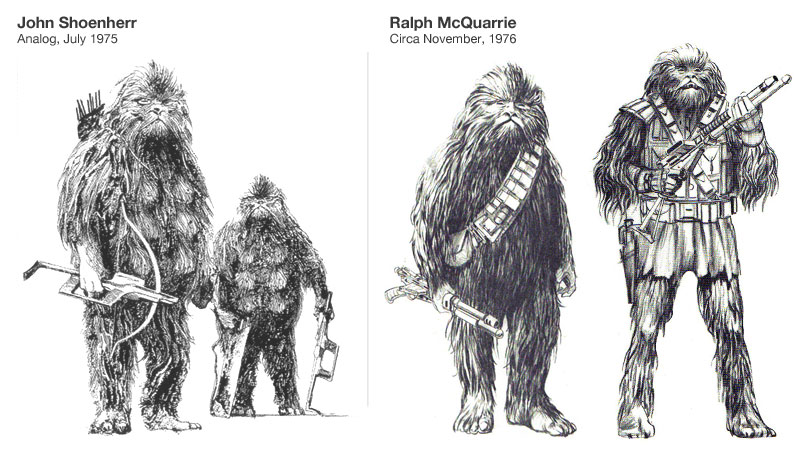

As is obvious from the following side-by-side comparison, the illustration McQuarrie is referring to wasn’t decades old, but months, being none other than this one by Dune legend John Schoenherr, from the July 1975 issue of Analog:

John Schoenherr's creature compared with Ralph McQuarries redesign of Chewbacca

Source: The Art of Star Wars, page 67.

Hmmm.

The drawing, as the cover below, was for a Hugo-nominated novelette by George R.R. Martin which: "[…] deals with the “realities of a very rigid society conflicting with what looks like a pushover primitive tribal society; and we find out where the strength really lies. It’s called ‘And Seven Times Never Kill Man’ (red. drawing its title from a Jungle Book poem by Rudyard Kipling).” [10]summary. A story which in itself is pretty familiar to the nature vs machine conflict surfaced in the early scripts and again in Return of the Jedi (although that's a theme so common by then that it's hard to say that this particular story had any explicit influence on Star Wars.

Analog, July 1975 cover by John Schoenherr

And as if that wasn’t enough, in another interview around the same time as the 2004 StarWars.com interview McQuarrie actually ends up contradicting himself:

Ralph McQuarrie: “We had an old 30’s illustration showing a hairy ape-like creature that George kinda liked.” … “We started out with the idea of him looking sort of like a lemur, and then I did one creature that had breasts down the front of him. I removed the breasts because it wasn’t to be a female, and I put a bandolier on there and gave him a weapon.” [2]charactersofstarwars

Here a clarification is in order, as several sources have pointed excitedly back to this post and summarizing this as: “Lucas told McQuarrie it was from the 30’s!”. There is no indication anywhere of that being the case. McQuarrie refers to it as being from the 30’s or from a 30’s illustrator, that is all.

While it is remotely possible that McQuarrie drew a wookiee with six breasts, unless kept in a vault in the exceptionally well-stocked Lucasfilm Archives, for fear of even more direct comparisons with Schoenherr’s work (it’s hard to get any more direct than the above I’d say), a 1975 drawing of a female wookiee would truly be a find!

In reality it’s more likely that McQuarrie over the years simply forgot the sequence and origins of things. Both of the contradicting statements are from interviews released in 2004; the featurette interview having possibly been done in 2003 or even 2002, and it’s possible that McQuarrie remembered in the interim more details of the creation.

Whatever the case, it’s hard to say what prompted the visual do-over. Perhaps Lucas — who devoured sci-fi books, comics, pulp magazines and spectacle action movies ad nauseum trawling for ideas — came across the magazine and simply found it a more compelling look. Most likely, he wanted to soften up the design now that Wookiees would no longer play their old role of barbarian jungle creatures, as Han Solo turned from being a green-skinned alien, an underground operative, in the first draft, to a human ‘free lance tough guy for hire’ in the second:

George Lucas: “[Han Solo] did start out as a monster or a strange alien character, but I finally settled on him being human so that there’d be more relationship between [Luke, Leia and Han]. That’s where Chewbacca came in as the kind of alien sidekick.” … “My original inspiration for Chewbacca was my dog Indiana. She was the one that sat there with me as I was writing the script all the time. She’d ride with me in the car as a co-pilot. And as she’d sit in the car, she’d be as tall as I am. She’s an Alaskan malamute, she’s very big. I thought that was a funny image.” [2]charactersofstarwars

George Lucas and his Alaskan malamute Indiana

Source: The Characters of Star Wars.

From Esquire, February 1975.

This anecdote’s probably true—except Indiana was Marcia's dog, not George's—it fails however to mention that Chewbacca was first an alien tribal prince on a jungle world, until the second draft, where the whole wookiee subplot has been excised, leaving a ‘creature’ vacuum to be filled, which is why he then became the first-mate to Han Solo. Strictly speaking Lucas isn’t bending the truth (his use of the word ‘originally’ is a bit far-fetched perhaps), but in the absence of the full history of the character, his anecdote might seem a plausible enough explanation.

As an aside, it’s interesting to note that Lucas rarely talks about bushbaby Chewie, perhaps because he knows that if he starts down that road, he might have to try and bridge the gap from that to the post-Schoenherr Chewie, which he can’t do without admitting that it was essentially borrowed wholesale.

Regardless Lucas obviously found the Schoenherr creatures a good match, and the influence is obvious; down to the crossbow come bowcaster (which seemingly has no design iterations to speak of, having probably been done ad hoc by the prop department). Aspects of it changed for the final film, as we’ll see shortly, but it’s clear that with the exception of a single surviving bandolier, Chewbaccas design from here on out was clearly based on Schoenherrs work.

As the drawings are all undated, it’s hard to pin down when this change took place. But in late November, 1975 [p. 66, 9]rinzler2007 McQuarrie painted the following production painting in which, though small and with his back turned, Chewbacca appears almost as on screen. McQuarrie could turn around a painting like that in a few days, so the change could have happened as late as early November.

Chewie pretending to be a prisoner by Ralph McQuarrie

Source: The Art of Ralph McQuarrie, page 178.

Notice that as in the scripts, and McQuarries previous paintings (and coincidentally also on Schoenherrs cover), Chewies fur in the above painting is still grey.

Costume designer John Mollo and creature designer Stuart Freeborn came onboard in January 1976. Freeborns first project was Chewbacca, which implies that the following (poorly scanned by me) drawings by Mollo, were probably done right as they came onboard. Mollo most likely decided on the palette change to make Chewie stand out next to Han and the Falcon, both of which are kept in neutral tones. This is the first time he sports his brown and grey coat of hair, but other than that, there’s little change in design (any differences should probably be probably be attributed to Mollo’s rendering, not to new design directions).

Chewbacca color schemes by John Mollo

Source: The Making of Star Wars, page 135 / Chronicles of Star Wars, page 90.

Interestingly, despite all of these changes to the design, the revised fourth draft from March 15th, 1976 — the shooting draft — still uses the now outdated bushbaby description, though the wording has softened up his fearsome looks slightly:

Ben is standing next to Chewbacca, an eight-foot-tall-savage-looking creature resembling a huge grey bushbaby monkey with fierce baboon-like fangs. His large blue eyes dominate a fur-covered face and soften his otherwise awesome appearance. Over his matted, furry body he wears two chrome bandoliers, and little else. He is a two-hundred-year-old Wookiee and a sight to behold. [11]fourthdraft

Notice that the fur color has been removed. And while it’s odd that the flak vest and brown shorts are missing, but two bandoliers and the bushbaby face remain, by this time the chaos of the ramping production and the impending shooting schedule probably made such matters trivial.

For his first three or four weeks, Freeborn worked alone on the movie’s most important prototype, Chewbacca, creating concepts and masks based on McQuarrie’s design. He was joined by his family and assistants as the load increased week by week. [p. 111, 9]rinzler2007

McQuarrie notes on the changes between his ultimate sketch and the final design:

Ralph McQuarrie: “Well, to me it seemed [Stuart Freeborn] added a jawbone from one of the ape creatures he did for 2001: A Space Odyssey in the creation of Chewbacca’s chin. Mine doesn’t have a chin and his does, which is very important to the way it ultimately appears.” [6]starwarscom

Interestingly, Lucas has a more holistic view of the final design:

George Lucas: “We didn’t really have the ability to do animated characters at that point, so I made the decision with Chewbacca that he would be a large man in a suit. So [Stuart] tried to take what Ralph had drawn and interpret it to use Peter Mayhew, and he is a certain structure, has a certain way of walking, he has certain eyes and taking his actual skeletal structure and turning that into a costume and a face that would mechanically work, and that changes the design, just by the nature of the reality it changes it. Whenever you have a design concept, and you put it into reality, most of the time, especially in the early years, it would change everything.” [2]charactersofstarwars

But more than that, it sounds like the design was kept fluid up until the last day:

Lucas would often pop in to see how Stuart Freeborn was doing on his first project, Chewbacca the Wookie, which he was making from straight yak hair (Freeborn’s sketches, which bear some resemblance to the man, also below). “I would go in there every day and push the nose around a little bit and push the chin up,” Lucas says. “I kept pulling the nose out and pushing it back. It was difficult, because we were trying to do a combination of a monkey, a dog and a cat. I really wanted it to be cat-like more than anything else, but we were trying to conform to that combination.”

“Chewbacca was a fascinating one,” Freeborn says, “because he had to look nice, though he could be very ferocious when he wanted to be. It was fun making a monster that looked friendly and nice for a change, instead of being menacing. I had seen a sketch [by Ralph McQuarrie] and I based it on that because it was very good, and it looked just right to me.” [p. 113, 9]rinzler2007

Stuart Freeborn's Chewie sketch.

Source: The Making of Star Wars, page 113.

Stuart Freeborn at work on Chewbacca.

Source: Unknown.

In the early morning hours on Monday, April 12th, 1976 on stage 3 of Elstree studios in England, then the home of Mos Eisly’s Docking Bay 94 (and later rebuilt into the Death Star docking bay) and one certain Corellian hunk o’ junk, Peter Mayhew and Harrison Ford stepped in front of the camera for scene AA53, ‘Jabba and Han Solo in docking bay’, their first.

"I'd rather comb a wookie!"

Source: Unknown.

The rest is history.

But then that scene was reshot the following Wednesday and then subsequently cut, probably for technical, maybe for budgetary concerns. Then mauled by horrific special effects in the special edition re-release. And again the 2004 DVD release. And then lovingly restored to its original state from scraps by Garrett Gilchrist, a fan.

But the rest is history.

Have you ever noticed how Chewbacca doesn’t actually do anything in Star Wars (much like Leia, the human McGuffin)? As a prince on Yavin in the early drafts, he had a role to play, but even Lucas admits openly that he was a ‘kind of alien sidekick’. And other than being the point man as Han picks up chicks in fringe star systems, Chewie does little more than tag along and man the Falcon while Han is off playing hero at the guns. He could be replaced with an autopilot, and the story would unfold largely the way it did with him in it (provided that Han himself hooked up with Obi-Wan).

The real reason he’s there at all, is simply to provide flavor, since as the story evolved there was no longer use for aliens outside of the Mos Eisley cantina.

But Star Wars without Chewie? What a bore.

Star Wars is well known for its more famous sources of inspiration — Kurosawa, Sergio Leone, Flash Gordon — but even so there are many touches about it that are often thought of simply as blessed (a karma account brutally balanced out by the prequels). I wrote this post first because I thought I’d found a covered-up missing link in John Schoenherr’s work for Analog — still conveniently ‘forgotten’ — but as I started writing and researching the story, aside from the occasional comparison with between Chewie and Schoenherrs creatures, it struck me that while this wasn’t something that had seen a lot of exposure, more strikingly I had in fact never read a proper chronology for how Chewbacca came together, not from fans, not from official sources.

And by putting this together, more importantly, I suddenly found myself in familiar territory.

Chewbacca didn’t spring to life out of nowhere, fully formed when Lucas saw his dog in the passenger seat of his car. That’s the soundbite. A single step. The reality is complex and human. From vague names floating around, the kernel of an idea, changing purposes and roles of characters, major restructuring, the design hopping from person to person, scrapping the existing concept and going down a different path, seeing existing things in a different light and having to conform a range of ideas to complement and enrich one another.

The familiar territory I found myself in was the creative process. I saw the struggles we’ve had on the games I’ve worked on, how some influences would change entirely and others would cruise straight on through to the final product and even the decision making process I’ve gone through on my own projects. It’s a never-ending series of often mundane and very down-to-earth practical decisions, often enough to make you lose sight of the big picture.

It’s makes one breathe a sigh of relief; Star Wars wasn’t a mystical, muse-favored event; an all-powerful force of unbridled inspiration. It puts its pants on one leg at a time, just like everyone else.

But where it differs, is in having the talent, the vision and more importantly, the willingness to say: “This isn’t good enough. This isn’t what I’m looking for”, while keeping the larger picture in mind. It happened with Chewbacca, the Millennium Falcon (a story for another time) and even the scripts themselves. All one has to do is take bushbaby chewie, green-skinned Han, Cantwell’s first Millennium Falcon and the first drafts, and Star Wars would be all but forgotten today.

It seems fitting for an article built on other people’s work to finish with someone else’s conclusion. And a friend of mine, and fellow McQuarrie-fan, Kiel Bryant upon reading this wrote to me in a mail:

Kiel Bryant: I’m dismayed by the cult of originality — it sets up impossible, false expectations which fail to grasp what art is. Innovation is good, exploration is to be encouraged — they build on what’s gone before — but more often than not it’s enjoyable to simply experience an idea well-conceived, regardless of that idea’s source or its “originality.” And in the final analysis, were Star Wars or [Raiders of the Lost Ark] ever intended to be wildly original? No, they’re pastiche — valentines to the swashbuckling genres of yore. Kids, especially millennials, make a simple and honest mistake borne out of youth: they see Star Wars before they’ve seen its inspirations and assume it came that way fully assembled, direct from Lucas’ head. They witness result, not process. Then, growing as artists or cinephiles, their awareness gradually enlarges, the supporting armature begins to show — and because the film wasn’t what they’d originally dreamt (a total creation, which is an impossibility), they decide George Lucas isn’t worth the praise they originally foisted on him. Absolutely circular, and absolutely pointless.

It is far easier to destroy than to create.

Luckily the pendulum of discovery swings both ways, and as easily as it can alienate the easily dissuaded, it can also send people down the road of discovery a film like Star Wars deserves. Uncovering the story and creative process behind it, is what keeps taking me back to this 33-year-old film, which you’d think by now had given up all of its secrets to the world.

And in that, I see myself, the people around me, our story and struggle with the same creative process and day-to-day problems. But to find those things, you have to look beyond the noisy anecdotes and creation-mythology it’s surrounded by, and you’ll find that any act of ‘creation’, from writing this post, to designing a website or even creating an iPhone, requires much of the same that went into creating a wookiee for a galaxy far far away.

Happy life day.

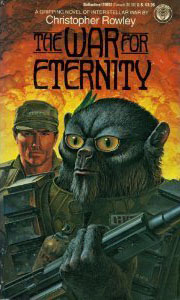

It’s worth noting that despite McQuarrie saying that: “While it may appear that the character was derived from my early Chewbacca designs, it was really taken from my cat” [p. 34, 12]artofmcquarrie about his designs for the cover of the non-Star Wars-related The War for Eternity, published in 1983, it is nonetheless hard to look at it and not see it as the final resting place of bushbaby Chewie.

Sketches for the cover of The War for Eternity by Ralph McQuarrie

Source: The Art of Ralph McQuarrie, page 34.

Cover by Ralph McQuarrie for The War for Eternity

Source: The Art of Ralph McQuarrie, page 35.

I first saw the Analog cover on Skiffy and found the interior illustration at Flooby Nooby.

And remember, Good artists borrow, great artists steal and Everything is a remix.

celebrationvphoto

thirddraft

chroniclesofstarwars

artofstarwars

analog:1975

thx1138

kaminski:2008

The official Star Wars website Millennium Falcon databank entry.

The Characters of Star Wars featurette from the original trilogy DVD set. Lucasfilm, 2004.

Marcus Hearn. The Cinema of George Lucas. Harry N Abrams Inc, 2007.

Artifact From the Future: The Making of THX 1138 on the THX 1138 DVD. Lucasfilm, 2004.

George Lucas. The Star Wars: Rough Draft. May, 1974.

Ron Magid, Ralph McQuarrie on Designing Star Wars. The official Star Wars website, September 20, 2004.

Laurent Bouzereau. Star Wars: The Annotated Screenplays. Titan Books, 1997.

George Lucas. The Adventures of The Starkiller (Episode One). “The Star Wars, Second Draft”. January 28, 1975.

J.W. Rinzler. The Making of Star Wars: The Definitive Story Behind the Original Film. LucasBooks, April 24, 2007.

Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact, Volume 95, Davis Publications, 1975.

George Lucas. The Adventures of Luke Starkiller, As Taken From the ‘Journal of the Whills’ (Saga 1), Star Wars, Revised Fourth Draft, Shooting Script. March 15, 1976. It rolls off the tongue.

Ralph McQuarrie. The Art of Ralph McQuarrie. Dreams and Visions Press, 2009.

Celebration V photo (2010) by popculturegeek.com

George Lucas. The Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Starkiller, Third Draft. August 1, 1975.

Deborah Fine & Aeon Inc. The Star Wars Chronicles. Virgin Books, 1997.

Edited by Carol Titelman. The Art of Star Wars - Episode IV: A New Hope. Ballantine Books, 1997.

Art by John Schoenherr. Analog Magazine. Candé Nast, July 1975.

George Lucas. THX 1138. Lucasfilm, 1971. (Screengrab from the laserdisc edition).

Michael Kaminski. The Secret History of Star Wars. Legacy Books Press, 2008.