Alphaville undoubtedly went on to influence the full-length THX 1138, and though its influence is at first glance less on the student film, it seems likely that the very idea of its dystopian world originated with the unorthodox French science fiction film. Certainly, the techno-gibberish and the all-seeing computer seem to share some relation with it.

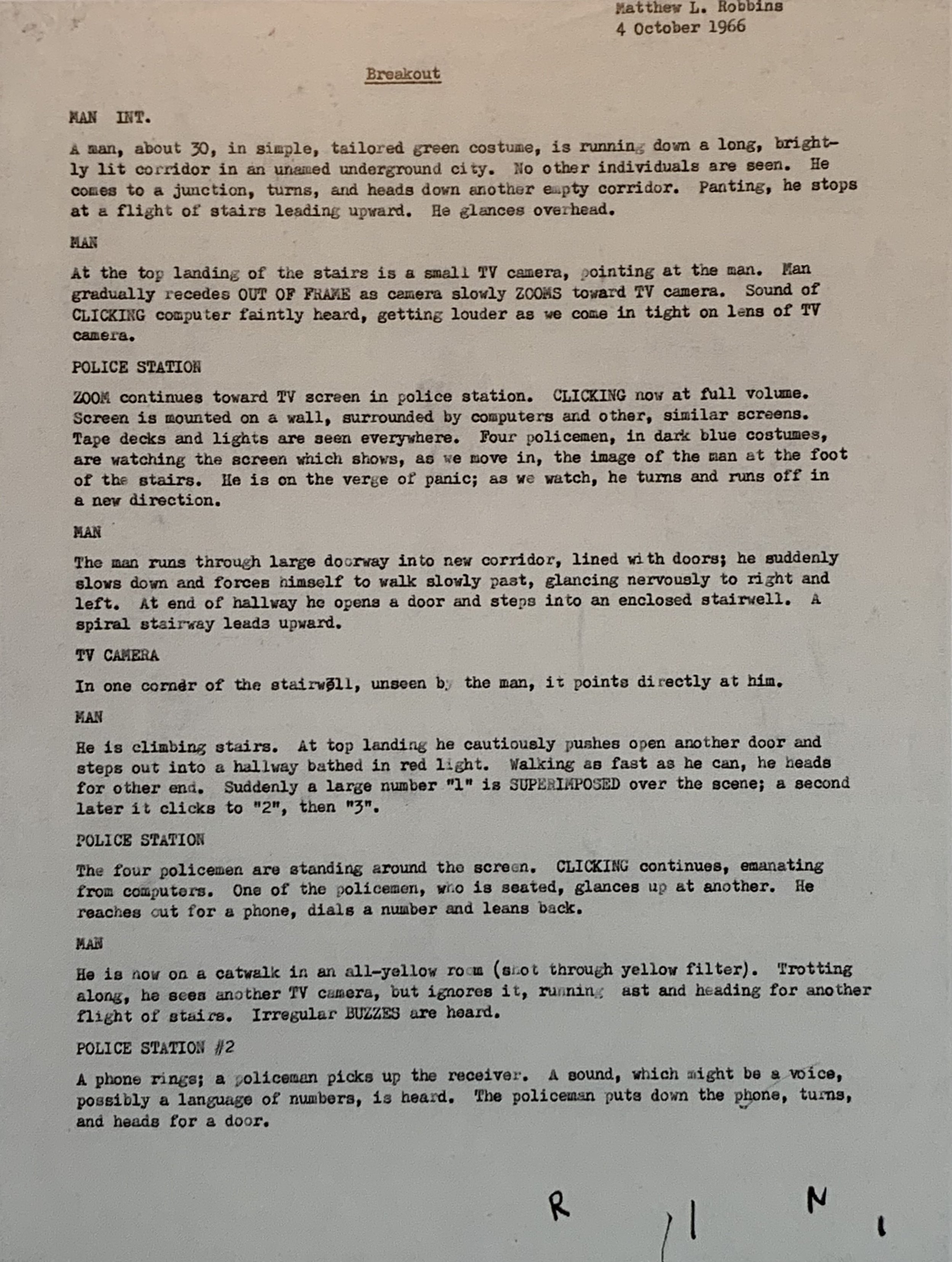

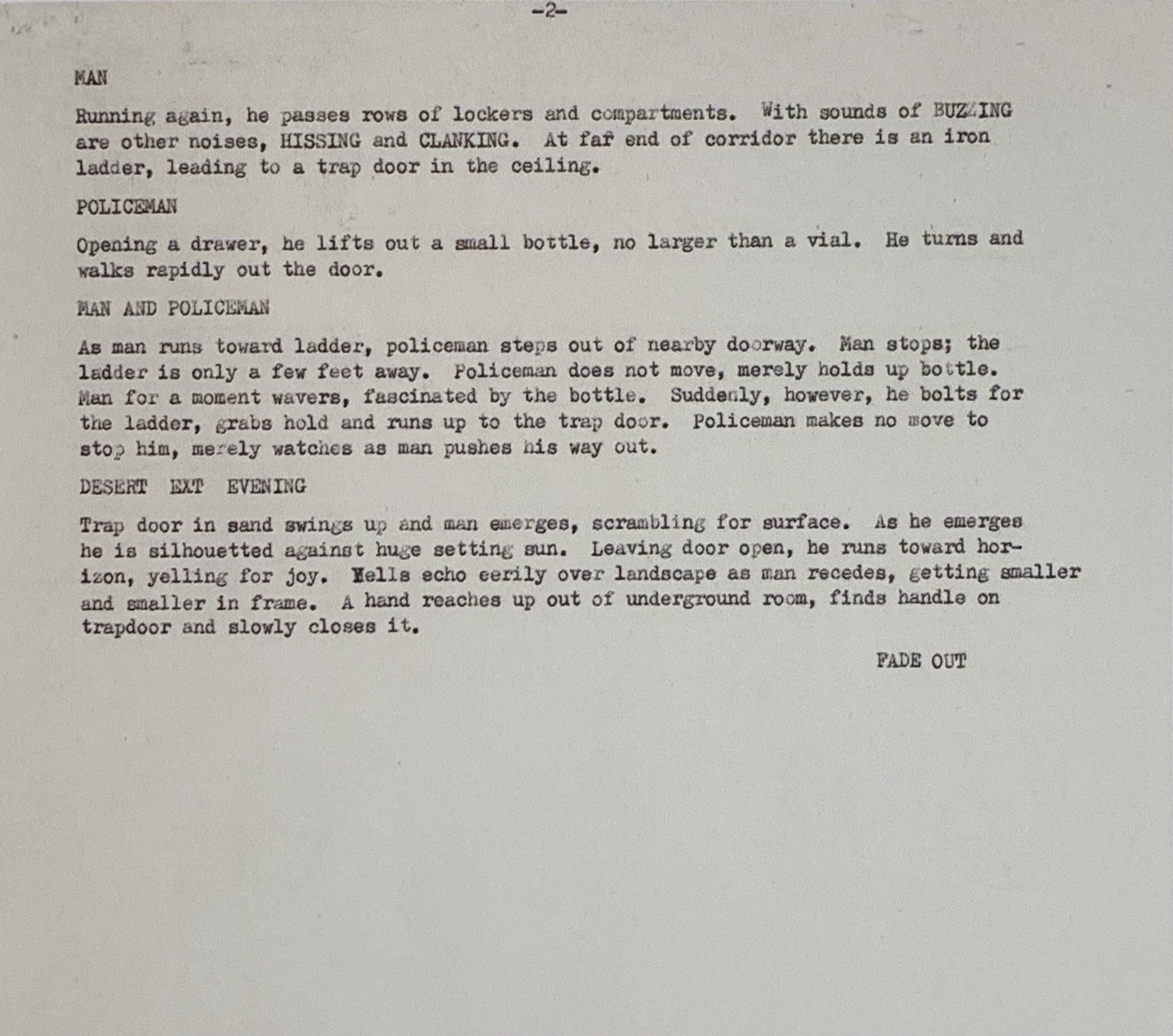

Based on a treatment written by Lucas’s classmate, and future collaborator, Matthew Robbins, the basic premise of a man on the run from an oppressive society remains the same as in the feature-length THX 1138, even if the circumstances are abstracted. The setting change (and production size and quality) aside, there is one noteworthy alteration in the narrative, which is otherwise as straight-forward as that of Freiheit: THX actually escapes. Although a disembodied narrator, upon THX's escape, informs his mate that by doing so, he has effectively killed himself (damned if you do, damned if you don’t).

In the space between Freiheit, in which the hero has no chance of winning freedom and Star Wars, in which the hero wins freedom, both for himself, but also for the galaxy, THX 1138 escaping into the real world, is Lucas’s first move from one extreme to the other, over the course of the following decade.

Another noteworthy change is from the militant oppressors of Freiheit to the surveillance society of Electronic Labyrinth. No one is physically hunting THX 1138 — the chase is through cameras and, symbolically significant, rather than using machine guns, they attempt to stop him using a ‘mind-lock’ — a student film metaphor for conformity and anti-authoritarianism if ever there was one — which backfires, causing one of the pursuers to utter, in amazement: “Incredible”.

The message is clear; through the sheer force of will, escape is possible. And contrary to the message of Freheit, Freedom can be won (even if in the eyes of the system it equals death).

As an interesting footnote it's worth noting that in Robbins’s treatment one of the pursuers tries to stop what was then only referred to as ‘the Man’ from escaping out into the world, by showing him an unexplained vial, presumably a drug, a theme which made it into the feature-length remake. Fear of the government using drugs to suppress its people was after all a classic 1960s conspiracy theory and fit in perfectly with the ‘freedom of the individual’ themes that run throughout Lucas’s work.

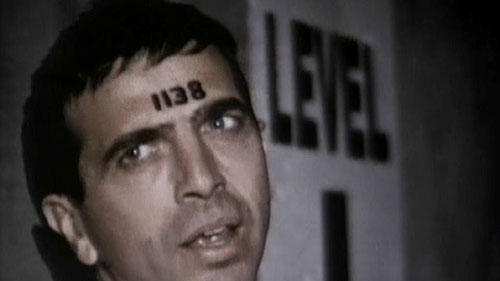

A Jesus idol, the number ‘0000’ written on his forehead, is overlaid for a second or two during Electronic Labyrinth, hinting at one of the prevalent images and themes of its feature-length older brother, THX 1138, and one of the devices Lucas would carry with him over into both American Graffiti and Star Wars. ‘0000’, the first number, and the non-number, the origin and the nothing, which in a world where people are numbered seems an obvious reference to a first being; perhaps to the divine origin of men? Ah, pretentiousness and film studies, forever intertwined.

Electronic Labyrinth was Lucas’s last film before he graduated USC.