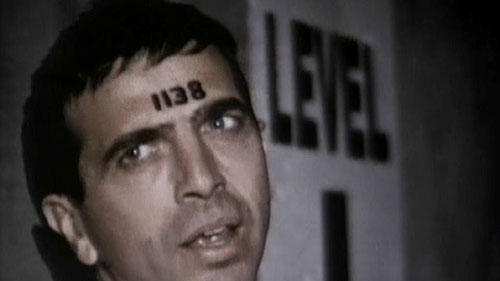

Except of course, where Buck Rogers is unapologetically heroic in the fight against the evil Mongol Reds, on behalf of ‘the greater good’, THX is decidedly unheroic, fighting only for himself, and for no reason ever articulated. In fact, he seems entirely incapable of carrying the burdens of the collective, leaving in his wake LUH, his lover, the devious but protective SEN, and even the child-like and helpless hologram. He can’t carry anyone but himself to safety, and even he only manages by the skin of his teeth. This scared and naive individual prevails, but at the cost of everything he had; a price which the film posits, may be necessary to pay for individual freedom.

On the other hand, the message of THX 1138 could be read as a call for attention to exactly the kinds of people not usually thought of as heroic. Chewed up by, and incapable of living inside the norms, the misunderstood must carry the burden of being different or suffer expulsion from a system more interested in homogeneity than individualism. Michael Korda in the introduction to his book on Lawrence of Arabia, aptly named Hero, says:

We have become used to thinking of heroism as something that simply happens to people; indeed the word has been in a sense cheapened by the modern habit of calling everybody exposed to any kind of danger, whether voluntarily or not, a “hero.” Soldiers—indeed all those in uniform—are now commonly referred to as “our heroes,” as if heroism were a universal quality shared by everyone who bears arms, or as if it were an accident, not a vocation. Even those who die in terrorist attacks, and have thus had the bad luck to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, are described as “heroes,” though given the choice most of them would no doubt have preferred to be somewhere else when the blow was struck.[1]

Even the THX of Lucas’s student film was pronounced “Incredible!”, while the THX of the feature film gets no such recognition. He may be “just an ordinary, normal human being who keeps his wits about him” (barely), but is he a hero?

Beyond the thematic content of THX, which while delivered in a layered, complex, almost abstract manner is as simplistic, if antithetical, as that of Star Wars, there are many points of similarity between the structuring and aesthetics of the two seemingly wildly differing films. The abrupt division of acts as well as their discrete contents foreshadows those of Star Wars, first in the loss of LUH at the hands of some incomprehensible fate early in the story. The small group of ‘rebels’ escaping from a prison and making their way through the maze of the underground city. And the faceless ‘empire’ personified (or not) respectively by the chrome-masked robot police and the stormtroopers. In both cases it’s the individual vs. the system, whether the system is overly benign in its intention as is the case in THX 1138, or not, as is the case in Star Wars.

Most of all, the final pursuit through the tunnels can’t help but bring about the speed and urgency of X-wings and TIE fighters screaming past the camera in very similar tunnel pursuits. Whip-pans track the super-car and the robot police, radio-distorted voices talk pseudo-gibberish at the control center which follows the action from afar and neigh identical intercutting of internal/external shots. The parallels to the attack on the Deathstar are obvious, as are the differences: much less ‘action’, no shots fired, no explosions and a diametrically opposite purpose, flight, rather than fight. Regardless, for a sequence involving a car and two motorcycles driving through a tunnel, it manages to be spectacularly tense, an entirely cinematic achievement: camerawork, editing, and sound.

And though it’s much more willing to experiment and confuse its audience, playing with surveillance camera POVs or lingering on environmental details (a lizard at home amongst wires and circuitry), obviously less concerned with pace than with simply lingering, soaking up the world, the fittingly detached, observing camerawork of THX 1138 equally foreshadows the ho-hum mundanity later used to make the topsy-turvy world of Star Wars seem perfectly normal.

“[The] problem George and I found with science-fiction films is that they were like American films being made in Japan, which felt that they had to explain these strange rituals to you, whereas a Japanese film would just have the ritual and you’d have to figure out for yourself. So we though, ‘let’s make a film like that: that is, about certain trends that are present in the world today extrapolated into the future.[Murch, p38, 2]

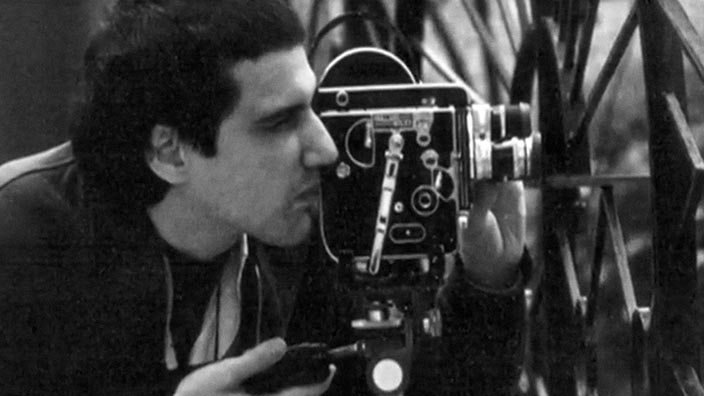

To be blunt about it, THX 1138 is perhaps the only film in which Lucas has properly exercised his belief in purely editorial and visual cinema – cinema púr – over dramatic or narrative cinema (as in the works of his mentor, Francis Ford Coppola). It’s a film concerned with creating an experience through collage of image and sound, by editing and layering, more than it is with the story or emotional state of its protagonist, who by virtue of the concept itself, is almost devoid of such and indeed even traditional narrative. As a result, THX 1138 asks of its audience attention and dedication, inviting intellectualization.

Alphaville (1965)